Mother Jones Special

Mother Jones:

"War is the total failure of the human spirit."

Daily Dispatches from the Lebanese Capital

Dahr Jamail

July 27 , 2006

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Ah, the joys of reporting on a shoe-string budget! I've been working the last few days with a freelance photographer from Holland, Raoul. It's always helpful to team up—both for the companionship and to split costs. Sometimes it's necessary, working in a war zone in a foreign country where you don't speak the language well enough to get by on your own, to hire a driver, interpreter, and fixer. So costs add up fast, on top of the hotel, feeding, and phones, which are always necessary.

Thus, Raoul and I once again hit the streets after deciding to split the costs of a driver. Not a professional driver, mind you, but one we hired on the cheap. This means he wasn't used to working for journalists.

He arrived late—long after the time we were supposed to meet the person we'd hoped to interview, so we jumped in the car and asked him to step on it.

Nadim, the driver, a skinny 29 year-old college grad who, like so many Lebanese, is without a regular job, slowly made his way over to the infamous Sabra refugee camp, where in 1982 Lebanese Christian militiamen massacred hundreds of innocent Palestinians.

My eyes dart back and forth between my watch and the road, as driving here always entails the obstacle course of scooters, women walking with children in tow, the odd dump truck hogging the entire road, and loads of other cars. Even though so many residents have long since fled Beirut, traffic is alive and well in many districts of the capital city.

Suddenly Nadim pulls over and opens his door. While he's halfway out of the car he barks, "I have to eat."

I hold my hands up and spin around to find Raoul doing the same. "What can we do?" he asks. We stare at Nadim as he waits patiently at a bread stand while I continue to glance at my watch, watching the minutes tick off.

Five ticks later Nadim is back and lowering himself back into his seat. "I was hungry," he says, turning the ignition.

Luckily for us, the guy we're here to interview, Ahmad, a co-founder of the NGO Popular Aid for Relief and Development (PARD), meets us with a smile near his office. We pay Nadim, coldly thank him for his time, and let him know we won't be needing his services again. (Raoul and I agree to use a taxi service later for the return leg.)

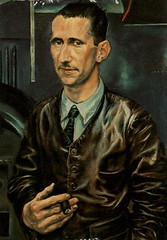

Ahmad Halimeh Ahmad Halimeh, is one of those people who is always smiling, and always busy as hell. He brings us tea and we talk in his office. He says, "Our NGO, originally designed to serve the Palestinian refugees here in Sabra camp with health and education services, is now 90 percent engaged in working to bring relief to the war refugees from the south."

With a staff of 20 volunteers and a few office workers, PARD is offering its medical services to over 100 families who were displaced from their homes in south Beirut and southern Lebanon. They are running a mobile clinic which is currently in the south, and also managing to find shelter for many of the families.

Our time with Ahmad highlights the dual nature of war—that it simultaneously brings out the worst in some human beings and the best in others. Ahmad and his organization are a bright spot in the darkness that has engulfed Lebanon, as the Israeli government has obtained a sort of eternal green light from the U.S. to carry on as long as it deems necessary.

"War is the total failure of the human spirit," says British journalist Robert Fisk, which I think encapsulates it better than just about anything I have heard.

But war forces humans to survive under seemingly impossible circumstances, and in these conditions some strive to help others when barely capable of helping themselves.

We talk with Ahmad for a couple of hours and then tour the camp where so many hundreds of innocent civilians were slaughtered in 1982.

Later in the afternoon I met up with my friend Hanin, a Swedish journalist of Palestinian descent, who'd just returned from two days in Sidon, 20 miles south of here.

"The bombs are everywhere, and there are thousands of families there with nothing and nowhere to go," she tells me. She was clearly traumatized after seeing bodies scorched by white phosphorous, and others cut to shreds by what were most likely cluster bombs.

After seeing similar atrocities in Iraq, I tell her what I knew of PTSD, and that she needs to get some sleep then start talking about what she saw.

"I spent time with a little girl who told me her brother and father were killed," she says, beginning to cry, "And the girl asked me if my brother and father were alive. I told her, yes, they were." She drops her head in her hands and weeps.

War is indeed the total failure of the human spirit. And unfortunately, the decrepit, despicable stench of this war is everywhere you turn in Beirut. And I wonder and wish and ask myself why people like Ahmad aren't allowed to govern. Instead they have to pick up the pieces generated by those who do.

Dahr Jamail is an independent journalist who spent over 8 months reporting from occupied Iraq. He maintains his own website at dahrjamailiraq.com

This article has been made possible by the Foundation for National Progress, the Investigative Fund of Mother Jones, and gifts from generous readers like you.

© 2006 The Foundation for National Progress

http://www.motherjones.com/news/featurex/2006/07/among_hezbollah.html

Washington's Latest Middle East War

Faced with an Israeli attack that is tantamount to war crimes, the American peace movement must do more.

Phyllis Bennis

July 27 , 2006

Article created by The Institute for Policy Studies.

The Israeli war against Lebanon and Palestine, euphemistically depicted as “self-defense” against Hezbollah and Hamas, is simultaneously an Israeli war for domination, and a regional war to “remap” the contemporary Middle East. In this context it is as much a US as an Israeli war. The immediate trigger has its roots in the extraordinarily hypocritical US-led boycott and international sanctions against the Palestinians that started after the democratic election of the Hamas-led Palestinian Authority government in January 2006. And beyond the specific trigger, this new war was set in motion by the example presented in Washington’s Iraq-centered efforts at militarized regional transformation in the guise of “democratization.”

It must be stated unequivocally that this is a war against civilians – there is nothing “collateral” about it. And Israel is responsible for this war. Hezbollah’s July 12 raid across the Israeli border may have violated the 1949 armistice agreement between the newly created state of Israel and Lebanon, but it was limited to a military target. The only Israelis killed or captured were soldiers. Given the human devastation of the predictable Israeli response, the raid may have been what French Foreign Minister Philippe Douste-Blazy called it, an “irresponsible act.” But it did not violate international law. According to Human Rights Watch, “the targeting and capture of enemy soldiers is allowed under international humanitarian law.” It was Israel’s response, on the other hand, that escalated to a full-scale attack on civilians and civilian infrastructure starting with the bombing of the Beirut international airport. That act was what Douste-Blazy, distinguishing it from Hezbollah’s raid, called “a disproportionate act of war.” The Israeli attack stands in stark violation of the Geneva Conventions prohibitions against collective punishment, targeting civilians, destruction of civilian infrastructure and more. The attack was – and remains – a war crime.

The distinction is important. The Hezbollah attack on the Israeli army post and the failed Israeli attempt to grab back the captured soldiers, constituted a border skirmish. Such cross-border clashes happen around the world on a daily basis; certainly the Israeli-Lebanon border itself has seen more than its share. But a border skirmish is not a war – it’s a border skirmish. It only becomes a war if one or the other party wants it to escalate. In this case, there is no question that Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and his government wanted a war. The San Francisco Chronicle and other mainstream media have highlighted the fact that Israel had had this strategic plan in place since at least 2004, perhaps having started it as early as 2000 when Israeli troops pulled out of Lebanon. Israel was waiting for an appropriate time – or an appropriate pretext – to launch it. This moment, this pretext, they deemed, was the time.

US and Israeli Goals

It is telling that both Israel and the US have admitted they do not want a ceasefire. Their goal is an unequivocal military victory, not a diplomatic solution, regardless of the human consequences (and for Israel, regardless of the fate of their iconic but now much more-endangered captured soldiers). Israel appears to believe that it is possible to defeat a popular insurgency with conventional military means, despite a century of colonial history proving precisely the opposite for the US in Viet Nam, the French in Algeria, the British in India, and so many others.

Tel Aviv’s goals are to establish unchallenged and unchallengeable military control on all its borders, perhaps including a direct on-the-ground occupation, to wipe out all existing or potential resistance to its domination, and to transform the strategic map of the Middle East. Sound familiar? The approach was first articulated in 1996 when a group of former US officials drafted a strategy paper for Bibi Netanyahu, then running for prime minister in Israel. The paper was titled “Making a Clean Break: Defending the Realm,” and it essentially proposed for Israel a Middle East regional version of what the neo-conservative Project for a New American Century, and more importantly the Bush administration’s 2002 National Security Strategy, envisioned for the US on a global level. The essence of all these plans called for the dominant power to establish such overwhelming military control that no existing or future resistance could ever even imagine a challenge to that domination.

In the first few days of the crisis, a potential crack appeared between the Israeli and US aims. Israel’s goals were (and remain) primarily military, focused on wiping out any remnant of Hezbollah’s and Hamas’ power and influence across Lebanon, Palestine and the region. Simultaneously it hoped to bring the fragile holding-on-by-its-fingernails Lebanese government, already in thrall to Washington since the US-orchestrated departure of Syrian troops last year, even more completely under Israeli control. In Gaza Israel was trying to diminish even further the capacity of the already weakened Palestinian Authority. Parts of the Bush administration at that time, at least briefly, seemed to place a higher premium on maintaining the fiction that the Syrian withdrawal from Lebanon had set the stage for real “democracy” there, and maintaining something resembling stability in Lebanon remained a crucial propaganda goal. That led to the slightly mixed messages of the first couple of days, in which “Israel has the absolute right to defend itself” was tempered with “but they should be careful not to weaken the Lebanese government.” That ambiguity, however, did not last. By the third day or so, the Bush administration had largely abandoned any claimed concern about Lebanon’s fragile “democracy,” (there was never any concern expressed for Lebanon’s people) and had moved into full-scale unequivocal embrace of Israel’s aggression, rejecting calls for a ceasefire as “untimely.”

What Does Washington Want?

The actual US goals do not include a rapid ceasefire. Rather, Washington is committed to the same kind of regional remapping of the Middle East that Israel’s military assault aims for. The Bush administration began this process through its invasion and occupation of Iraq, and its support for Israel’s crusade reflects the same disdain for civilian casualties that the US has shown in Iraq. While some of the Iraq War’s key neo-con players are now out of the White House (Paul Wolfowitz at the World Bank, Douglas Feith at Georgetown, Scooter Libby on trial, etc.), it is clear that at least part of their intellectual legacy – the unilateralism, disdain for diplomacy, assertion of military power over all – remains in place. What Israel is doing now, with full US support through military and economic aid, diplomatic protection, and political support, aims to remap a “new” Israeli-dominated Middle East. That goal is fully in synch with the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, which aims to reconstruct a region without a hint of resistance to absolute US control.

For Washington, Israel’s war escalates the pressure on Syria and Iran, and it is likely the US will continue to take a direct role. There were complaints that the US evacuation of American citizens was slow; that may be less about inefficiency than about a US insistence on bringing warships up to the Beirut coastline to “escort” the evacuation ship. We may see those ships remaining off the Lebanese coast for quite some time, as an additional message to Syria and Iran, as we may see a longer deployment of the marines currently on-shore inside Beirut, assisting the evacuation.

At the United Nations

Also indicative of Washington’s strategy was the US veto of a ceasefire resolution at the United Nations, squelching any possibility of an early international call for an end to the killing. At this point, despite extensive discussion and widespread calls for a ceasefire, the US opposition to a ceasefire has largely paralyzed the Security Council. The secretary general has presented a set of recommendations that, while flawed in some respects at least begins with a call for an immediate “end to hostilities,” even if not an official ceasefire. Other UN officials, including humanitarian Jan Egeland and High Commissioner for Human Rights Louise Arbour have spoken of war crimes being committed, and called for an immediate end to hostilities. Several leading Non-Aligned countries have indicated other international initiatives might be under consideration as well, perhaps leading to a call for creation of an international “Coalition of the Willing to Stop the Killing.”

The US and Israel appear to be considering a UN proposal that would send international troops – “not UN Blue-helmets,” according to US Ambassador John Bolton – to the region. While the call for international protection is a longstanding regional demand, the version under discussion now would be far too one-sided to answer the real need. It would essentially impose a new occupation of south Lebanon, albeit by international, rather than Israeli troops, its mandate would include forcible disarming of Hezbollah while doing nothing to rein in Israel’s attacks, and it might even be based on NATO, rather than UN troops.

Regional Implications

It is clear that Hezbollah’s role in the crisis is leading to a qualitative escalation in regional support for the organization. Inside Lebanon that translates to greater support for Hezbollah’s social and political program, and its electoral role in the Lebanese parliament, as well as wider backing for the idea that maintaining Hezbollah’s militia separate from Lebanon’s national army might just be a good idea. In the region as a whole, Hezbollah is gaining popular acclaim for its role in supporting the Palestinians (specifically in trying to improve Hamas’ chance for a prisoner exchange) and most importantly, in challenging Israeli military domination. At a moment when Arab governments across the Middle East remain feckless and silent in the wake of escalating attacks, and people across the region grow increasingly angry about their own governments’ seemingly complicit silence, the ability of Hezbollah to go head to head with the Israeli military inevitably brings supporters and converts. This shift in regional consciousness is also reflected in what some Arab analysts are identifying as an “end to fear” among Arab populations,

The Bush administration, seeming to recognize this, has reportedly based the plan for Condoleezza Rice’s July 23rd trip to the region on the launch of an “Umbrella of Arab Allies” in explicit opposition to Hezbollah. The rising influence of the Lebanese resistance movement, along with that of Hamas, has created serious challenges for pro-US Arab leaders, who are already viewed with scorn by significant sectors of their population. With the televised images of the Hezbollah guerrillas taking on Israel, and the dramatic scenes of Palestinian and Lebanese victims of Israeli bombings fresh in people’s minds, the unwillingness and/or inability of Arab governments to do anything to help the Palestinians and Lebanese, let alone to challenge Israel on their own, stand as a sharp indictment of those regimes throughout the Middle East.

A consequent problem, of course, is that the current scenario also encourages a widespread belief –a dangerous illusion, in my view– that it is possible for the resistance movements overall to actually defeat Israel militarily. Certainly it is true that 18 years of Hezbollah’s resistance to Israeli military occupation in south Lebanon did force an Israeli withdrawal. But that example had many particularities that no longer prevail – not least that it took place before September 11, when the US regional involvement was very different, and that Israel’s commitment to Lebanon never matched that of its strategic dedication to Palestine.

The Iraq war has already begun to transform political and social consciousness in the region, and there is the potential that some in the region would look at how resistance forces there have fought the US military to a standstill, and imagine that small independent groups of militants might follow that “model” to win against Israel in Palestine as well. Again the distinctions – including the fact that the Iraqi resistance inherited the disparate weaponry of an entire army– outweigh the similarities. What remains similar is the increasingly parallel level of destruction in both Lebanon and Iraq.

Washington's Arab Allies

On a political level, the current war in Lebanon is also transforming the region, to the detriment of the existing Arab governments. It is remembered with pride and anger across the Middle East that in expelling the Israeli troops from Lebanon, Hezbollah was the first Arab resistance movement to force Israel to retreat, something no combination of Arab governments could ever do. At least as of the third week of July, there is a widening and increasingly visible divide splitting the Arab states.

On the one hand are those governments who see Hezbollah’s rising influence as a threat to their own power and are willing to condemn Hezbollah and at least tacitly support the US-Israel alliance, including Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. On the other hand are those governments more worried about losing power and control of their own populations who are all adamantly anti-Israel and pro-Hezbollah, who are claiming (disingenuously or not) to support the Palestinian and Lebanese against Israel. Those include Syria of course, whose government has remained quiet and largely afraid to move because of US threats even while public pressure mounts demanding public support for Hezbollah and the Palestinians. That group also includes non-Arab Iran, whose government has been very careful in its response, claiming that it would respond to an Israeli attack on Syria, but remaining conspicuously silent about its own role vis-à-vis the attacks on Lebanon.

A recent and surprising addition to the critic-of-Israel contingent is Iraq’s President Nouri al-Maliki. The defection of the Iraqi leader from the US camp represents a significant defeat for the Bush administration’s Lebanon plan. Chosen in a US-orchestrated election held under continued US military occupation, al-Maliki had earlier promised to demand a timeline for withdrawal of US troops from Iraq, but he never made good on that promise. Ironically, even Lebanon’s own Prime Minister Fouad Siniora, long understood to be a product of Washington’s anti-Syria “democracy” crusade, seems to have moved out of the pro-US camp, taking a clear we-will-fight-alongside-Hezbollah position in response to the Israeli threats of a massive ground invasion of Lebanon. Other powerful Lebanese parties have also announced support for Hezbollah, undercutting longstanding efforts by successive Lebanese governments to suppress its influence. Elsewhere in the region, individual politicians in pro-US Arab states including Saudi Arabia have begun efforts to distance themselves from their own government positions.

And For the Palestinians

In Gaza, the potential importance of the Hamas-Fatah unity process in the Palestinian Authority, shaped by the June acceptance by all sides of the “Prisoners’ Declaration,” has largely been diminished. Certainly the unity process remains important. But with one-third of the Palestinian Authority’s cabinet members and many of the Hamas members of the Legislative Council held in Israeli prisons as potential bargaining chips for a future prisoner exchange, and the US-Israeli orchestrated international isolation and sanctions of the PA still in place, the PA itself is barely surviving, hardly able to help its population cope with the ravages of the Israeli assault, and certainly not doing much governing. The Hamas-led government in the occupied territories also faces a political and credibility challenge from the external, Damascus-based leadership of the divided organization, who some believe have been more supportive of Hamas’ renewed military activity than the Hamas representatives in the internal government in Gaza and Ramallah.

In the meantime, the link between the Gaza crisis and the still escalating Lebanon/Hezbollah crisis, has brought Palestine back to the center of regional politics, away from its Oslo and post-Oslo identity as a narrower issue limited to the Palestinian West Bank and Gaza Strip alone. In the process of raising the profile and credibility of Hamas as the centerpiece of Palestinian politics, however, this trajectory has largely sidelined the importance and legitimacy of the Palestine Liberation Organization, or PLO. Hamas has never been a member of the PLO. As Hamas’ prestige, both within Palestine and internationally, rises, there is a danger that the PLO could be left behind – and with it, the representation of those components of the Palestinian nation who do not live in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip, most importantly the Palestinian refugees and exiles who now number more than 3 million spread around the world.

The Gaza-Lebanon Crisis and the Iraq War

How the new Lebanon crisis (Gaza and the rest of Palestine was of course already in crisis) is affecting the way the US is carrying out of its war in Iraq remains uncertain. But its impact on the wider militarization of the region has already become clear. The US has ratcheted up its provision of both emergency (jet fuel), and regular military equipment (including a batch of replacement “smart” bombs) to Israel. A New York Times article noted that analysts recognize US support for Israel in this war as equivalent to Iran’s support of Hezbollah. And the Bush administration just approved just $6 billion worth of new US arms sales to the nervous Saudi government, including Black Hawk helicopters, armored vehicles and other military equipment. The administration justified the sale to Congress claiming that the sale would help strengthen Saudi Arabia’s military and its ability to help the US fight terrorism around the world.

It is also clear that the murderous Israeli assault in Lebanon and Gaza, and their proud endorsement by the US, is ratcheting up even further the already sky-high Iraq-fueled levels of anger towards the US This may lead to another shift in the military situation inside Iraq, with US troops becoming even greater immediate targets. To the degree that sectarian considerations are shaping military outcomes in Iraq, it will not go unnoticed that while all of Lebanon has been made victim of this war, Lebanon’s Shi’a and the Shi’a-majority towns and cities of the south, already the poorest of the country, are suffering the most. Also, Hezbollah, now seen regionally as defender of not only Lebanon but Palestine and Arabs in general, is a Shi’a movement. However, the sectarian considerations are likely to remain secondary to the much broader concern that all Lebanese, including Sunni, Christians and all others, and all Gazans, who are overwhelmingly Sunni (as well as West Bank Palestinians, still suffering under occupation and international sanctions), have been made victims by a US-Israeli policy of all-out indiscriminate war against entire peoples.

Israel’s ground invasion of Lebanon, whether it becomes a permanent occupation or not, will certainly escalate the crisis further. This is particularly true of Israel’s declared intention to establish what Tel Aviv calls a “buffer zone” inside southern Lebanon. Israel has adopted the racist language of the Pentagon in Iraq, describing their goal being to “clean out” Hezbollah strongholds in south Lebanon, and then “hold” them to prevent a return. As Kofi Annan said on July 21, even if Israel “plans to say it’s a ‘security zone,’ for others it will be an occupation.”

The New War and the US Peace Movement

There is no question that overall, the escalation of the regional crisis to include all-out war in Lebanon and Gaza will make some work of the peace movement more difficult. It will be harder to call for bringing home all the troops from Iraq now, while the media propaganda focuses on “Israel under attack.” This is certainly true in terms of influencing congress or other policymakers, where the focus on Israel is escalating the existing Democratic Party leaders’ embrace of the Iraq war. And at a moment when key Republicans appear to be distancing themselves from the Bush administration’s war strategy, if not from the war itself, the new crisis is giving Republicans an opportunity to welcome the Bush administration’s position, while competing with Democrats over who can be stronger supporters of Israel. The unanimous Senate vote and the near-unanimous House votes supporting Israel’s war unequivocally and enthusiastically give some indication of that.

But we must never lose sight of the value, the legitimacy, the importance of non-violent struggle. As Americans our own history has seen our most important social victories – against slavery, for voting rights, for civil rights – won by mass mobilization and education. We can’t stop now.

We need to recognize and figure out why popular opinion has not matched the uncritical pro-Israeli cheerleading that has characterized mainstream politics. Higher percentages of the public are rejecting the close public embrace of Israel by the Bush administration, urging that the US “not engage” in the war. For many this means opposition to the US reengaging in active Middle East diplomacy. Missing, of course, is the broader understanding that uncritical US diplomatic and political support for Israel’s wars and occupations, along with more than $3 billion each year in military and economic aid, is the default position of US politics – whether or not the US leads the diplomacy, it is certainly “engaged” in the issue.

Polls indicate the public has a far more nuanced understanding than the politicians, with significant percentages critical of Israel. There is a small group of congresspeople, reflecting that more nuanced position, who have taken the [in this context] courageous decision not to join the groundswell of pro-Israel cheerleading, and voted no or present on the resolution. Many of those members and others are also supporting a new bill introduced by Dennis Kucinich calling for an immediate ceasefire.

One reason for the public willingness to recognize the devastation being caused by Israel’s war may, ironically, be mainstream television coverage. Despite the jingoism of many newscasters (though many TV journalists on the ground in Lebanon and Gaza have often been surprisingly even-handed), the graphic horror visible in the pictures is having a much bigger impact than the commentary.

The nature of the crisis, and the response to it demonstrates once again the need for education as the fundamental strategy of our movement. Certainly we have to engage with those in power, and immediate protests are important – bird-dogging Bush, Rumsfeld, Rice and other members of the administration to demand a ceasefire; sit-ins in the offices of pro-war members of congress; demonstrations against war crimes at Israeli consulates or the White House; informational picket lines outside media outlets perpetrating lies. Those demonstrations are also important as a message to people in the Middle East, especially in Lebanon and Palestine, just as has been the case in Iraq, that there are Americans who say no to the Bush agenda, who reject the militarism and unilateralism and lack of democracy that give rise to these wars.

And we must do more. We are faced once again with an American public willing to accept a media-driven definition of the crisis – accepting that it began with Hezbollah’s July 12 raid to capture two Israeli soldiers. Most Americans do not recognize that even this very specific crisis began much earlier, with the US-led international isolation and sanctions against the entire Palestinian people after the election of Hamas, with the Israeli missile assault killing a Palestinian family on a Gaza beach, with the “targeted assassinations” that have killed more than 125 non-targeted civilians, with the assassination of the newly-nominated deputy minister in the Hamas-led Palestinian Authority. Certainly most Americans do not root this crisis in the seizure of the latest of 9,000 Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails, or the legacy of 38 years of occupation of Gaza, or the consequences of 18 years of Israeli occupation of south Lebanon.

We face an American public lacking the information to challenge the reversed chronology of the crisis that has become the assumed wisdom. Even though the New York Times’ own July 19 chronology and a July 24 article finally told the truth, almost no one in the US seems to grasp the actual sequence of this particular set of events. Hezbollah crossed the Israeli border and captured two Israeli soldiers – an attack on a military target. Israel responded with a failed attempt to get the soldiers back, and then escalated immediately to massive airstrikes on Lebanese civilian targets –first the southern bridges, then the Beirut international airport. Only then, after Israel had transformed a border skirmish into a war and escalated from military to civilian targets, did Hezbollah begin its own illegal firing of rockets against civilian targets, Israeli cities.

Instead the majority of Americans – steeped in longstanding beliefs that Israel is always in the right – remain convinced that Israel’s attacks in Lebanon were only in response to Hezbollah’s rockets hitting Israeli cities. As a movement we need to take responsibility for a broad campaign of popular education that will make it impossible for such widespread misinformation – let alone the even more profoundly missing historical context – to gain and keep its foothold in public consciousness.

This is a moment for the broad anti-war and anti-empire movement to strengthen its ties with the longstanding movements for Palestinian rights and against US support for Israeli occupation, for human rights and a just and comprehensive peace in the region. That collaboration will also insure, among other things, that we do not allow the absolute horror and the more visibly international character of the Lebanon war, to push the Gaza crisis and the continuing horror of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Arab East Jerusalem off the top of our agenda.

We have an especially difficult challenge ahead as we look at how the Israeli “axis of terror” framework is reviving the popularity of the “war on terror” framework in the US While opposition to the war in Iraq continues to rise, there is a danger that the Bush administration’s claims – that the war in Lebanon is against global terrorism escalating against the US and our friends – could reverse that trend. We need to take on the work of educating people about the nature of US policy, how it leads to war, and how the current horror in Gaza and Lebanon is very much Washington’s war. We have to remind ourselves and others how the illegal US war in Iraq is encouraging the view that invading and occupying another country is a perfectly legitimate replacement for diplomacy and negotiations.

This is an extraordinary moment of crisis, but also a moment of opportunity. The UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, Louise Arbour, has told the world that war crimes have been committed on both sides, and warned that political leaders of supporting countries could be held personally liable. Human Rights Watch investigators in Lebanon told NPR that they are investigating Israeli war crimes. We should take advantage of that opportunity to press for accountability of our own government for its complicity in Israeli war crimes by providing the military hardware, fuel and weapons to Israel, knowing that they are being used in violation of international and US domestic law. It is also an opportunity for us to build our ties with our counterparts in Europe, Latin America and elsewhere, as we press for international charges to be brought against top Bush Administration officials who may be complicit in Israeli war crimes; the model of Belgium, France, Brazil and other countries prohibiting accused war criminals from entering their countries should be something we struggle to apply to US leaders involved in backing the current war.

Our Country, Our War?

At the end of the day this is a moment we must acknowledge and come to terms with a great sadness. What does it say about the state of our nation that our top officials have abandoned diplomacy with such certitude? That they are building a culture that welcomes unimaginable violence? That they are using their military and economic power around the globe to kill, dispossess, impoverish, and disempower people, isolating the US people from the world by taking our nation to war and standing as an unaccountable Colossus astride the entire world? That they have abandoned international law in favor of the law of empire? What does it say about us, as a people?

And what does it say about our movement, and what we have to do?

Phyllis Bennis is a Fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, DC and of the Transnational Institute in Amsterdam. Her latest book is Challenging Empire: How People, Governments and the UN Defy US Power.

This article has been made possible by the Foundation for National Progress, the Investigative Fund of Mother Jones, and gifts from generous readers like you.

© 2006 The Foundation for National Progress

http://www.motherjones.com/commentary/columns/2006/07/washingtons_war.html

Reality Check:

What International Force In Lebanon?

For all this talk of a robust international military presence in southern Lebanon, none is going to materialize.

Jeffrey Laurenti

July 27 , 2006

Article created by The Century Foundation.

As Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and fifteen other foreign ministers depart from a stalemated meeting in Rome on shutting down the Israel-Lebanon war, the air is still hot with proposals for a robust Western military force that would deploy to Lebanon to back a ceasefire, keep the Israelis out, and disarm Hezbollah paramilitaries.

Such a force isn’t going to materialize.

The Bush administration was initially cool to an international force when U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and British prime minister Tony Blair proposed it last Monday. But Washington is beginning to see an international force as perhaps the only face-saving vehicle for Israel to step back from its escalating military campaign in Lebanon—a campaign that is evidently achieving little militarily but is undeniably generating a powerful global backlash against both Israel and the United States. The prospect of a new Israeli “security zone” in Southern Lebanon may only exacerbate that reality.

The Americans, of course, would prefer it to be a NATO force, but without U.S. troops—in other words, a European force under Euro-American command. Many Europeans fear that a “made in USA” NATO label might prove fatal in Lebanon’s volatile environment, inciting violent resistance from the country’s Shiite Muslims.

But the real problem is that Europeans simply do not have combat troops to commit, given their existing deployments in Bosnia, Kosovo, and Afghanistan. Most importantly, none of the European governments is prepared to put its troops into a shooting war against a well-armed Hezbollah resistance whose Arab street “cred” has been built on defying Israelis, not knuckling under to them.

If the highly motivated Israelis cannot disarm Hezbollah’s guerrillas with a furious military operation, the equally alien Europeans cannot expect to succeed—any more than American combat troops can disarm Iraqis. Not surprisingly, Europeans make plain they will only put their troops into Lebanon as peace-keepers, not war-fighters.

In other words, the Europeans are prepared to put in troops to supersede the existing U.N. force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) only if it is essentially just a larger UNIFIL. And even UNIFIL exposes them to serious casualties, as Tuesday’s strike on its outpost at Khiam reminds us.

The task of finally reasserting the Lebanese government’s authority over all of Lebanon—for the first time since the country became an unwilling refuge for Palestinian guerrillas after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war—cannot be achieved by Western arms, just as it could not be achieved by Ariel Sharon’s invasion in 1982. The only international forces that can effectively support the Lebanese government, build up its army, and secure the transfer to it of the sophisticated weaponry that Hezbollah militias have acquired will almost surely have to be Arab.

In short, while a Western force would be a lightning rod for murderous attacks by Islamic jihadists promised a quick path to paradise, Arab troops would not.

So the robust core of an international force in Lebanon would probably best come from the Arab world—perhaps from North Africa as far west as Morocco and Algeria, and probably from nearby countries like Egypt, Jordan, and perhaps Syria. Yes, even Syria: Damascus almost certainly needs to have a stake in this settlement, and a tiny Syrian contingent embedded in a large Arab force might salve many wounds. The League of Arab States also can take the lead role, in conjunction with the Arab forces, in facilitating the Lebanese political dialogue.

Arab forces alone cannot be sufficient, however. Israel and, most of all, Lebanon’s one million Christians will want a guarantee that Islamists cannot hijack the country. After all, Saudi soldiers steeped in Wahhabi puritanism are likely to be scandalized by Christian Arabs’ values.

So onto a robust Arab core it will likely be necessary to graft a wider range of militarily capable forces, ideally from the non-Arab Mediterranean—especially Turkey, Italy, France, and Spain. These forces might not be the ones deployed into villages riddled with Hezbollah militants, but they could provide a soothing security presence in less volatile areas and the logistical support for their Arab partners.

The European Union’s foreign minister, Javier Solana, has advanced the idea of a mixed European-Arab force, and significantly, Israeli prime minister Ehud Olmert has left the door open to one. But there is one last conceptual hurdle that has yet to be cleared: the most logical aegis for an international force composed of Arab and European contingents is the much maligned United Nations.

Certainly, a robust Security Council mandate under Chapter VII of the U.N. Charter is needed, no matter what multilateral organization or ad hoc group of countries takes charge of the force. But beyond legal authority, the United Nations has unique assets in heading such a mission.

First, the United Nations has a funding mechanism to cover the costs of an operation. All nations have to share the force assessments, in accordance with their relative wealth (in the U.S. case, 27 percent; the E.U.’s, 38 percent). In a NATO, E.U., or Arab League operation, those countries putting troops into Lebanon would also have the privilege of paying the expenses themselves—while the rest of the world freeloads. Reliable funding is one reason why U.N. operations have proved sustainable over time, while ad hoc operations dissolve as one country or another tires of the task and deserts.

Second, a U.N. operation guarantees input from major stakeholders. The United States could be frozen out of influencing an E.U. or Arab League operation; Russia and the Arab world would be excluded from a NATO-run operation. Moreover, if one troop contributor wearies of the responsibility in a particular mission, somebody—the secretary-general—has the job of finding replacements.

Third, in a mission as complex as transferring weapons and personnel from the control of militia commanders to the Lebanese army, unity of command is necessary. Having parallel forces that only intermittently communicate with each other can be a recipe for disaster. Fielding an operation with separate reporting lines for Arab and non-Arab contingents would be especially risky in a case where a determined spoiler might play one off against another.

To minimize friction and clashes, the international community needs to emphasize that the new force aims to facilitate an elected Lebanese government regaining control over its sovereign territory and achieving stability, in full implementation of the provisions of Security Council resolution 1559.

It is a sign of how far the Middle East has changed that Israelis can now view the prospect of Egyptian and Jordanian troops on their northern border with equanimity, even reassurance. It also suggests how, out of the wreckage of the current war, Israel’s negotiation of peace treaties with its eastern and northern neighbors can at last give full effect to the promise of a permanent peace that the Security Council demanded nearly forty years ago in resolutions 242 and 338.

Jeffrey Laurenti is senior fellow in international affairs at The Century Foundation.

This article has been made possible by the Foundation for National Progress, the Investigative Fund of Mother Jones, and gifts from generous readers like you.

© 2006 The Foundation for National Progress

http://www.motherjones.com/commentary/columns/2006/07/international_force.html

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home