Elsewhere Today (395)

Aljazeera:

94 Taliban dead' in Afghan offensive

Sunday 10 September 2006, 13:25 Makka Time, 10:25 GMT

Ninety-four Taliban fighters are reported to have been killed in fierce overnight clashes in southern Afghanistan, as Nato and Afghan troops continued their biggest anti-Taliban offensive yet.

Nato’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) said in a statement the Taliban fighters were killed in four different engagements from late Saturday into Sunday in the southern province of Kandahar.

Insurgents also suffered heavy losses when troops used artillery and close air support in a separate strike launched against them as they gathered to counterattack, it said.

"The counterattack was neutralised, inflicting severe losses on the insurgents," the statement said. The number of casualties was still being determined.

The strikes were part of the massive anti-Taliban offensive, Operation Medusa, which was launched on September 2 and has so far involved 2,000 Afghan and ISAF troops.

Danger zone

The latest deaths take the number of rebels announced as killed in the operation to 450.

Medusa is focussed on the Panjwayi district, about 35 km west of Kandahar city.

The district is one of the most entrenched strongholds in Afghanistan and has seen several deadly attacks on foreign troops and civilians.

ISAF said its forces had "also successfully disrupted insurgent re-supply routes around the area".

"By controlling routes and blocking insurgent rat-runs we are denying the insurgents the ability to safely reinforce their positions and bring in more ammunition, food and water," it said.

Elsewhere in Afghanistan on Sunday the governor of the southeastern Paktia province was killed when a bomber blew himself up outside the governor’s office in the provincial capital, Gardez.

Agencies

http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/DE7878A4-DC40-4500-8ADF-23DC6D0A8893.htm

allAfrica: UN Environmental Arm

Probes Dumping of Deadly Toxic Wastes

UN News Service (New York) NEWS

September 8, 2006

The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) is investigating reports that toxic waste dumped last month around Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire's biggest city, and already linked to the deaths of at least three people, may have been illegally exported from Europe.

Aside from the three reported deaths, about 3,000 others have sought medical help after inhaling fumes from the hazardous substances, stating they are suffering from intestinal and respiratory problems, as well as vomiting, nausea and nose bleeds, according to the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

The exact nature of the substances have not yet been determined, but OCHA quoted "various sources" saying they were dumped at a number of sites around Abidjan - including the city's lagoon and its sewage system - from a vessel, Probo Koala, on 19 August.

Following a formal request from the Ivorian Government, UNEP said it would conduct an investigation through the Secretariat of the Basel Convention on the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal, which it administers.

The Secretariat is probing whether the Basel Convention's trust fund can be used to help pay for the clean-up operation, which could cost more than $13 million. It is also studying where legal responsibility for the crisis may lie.

UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner said "the disaster in Abidjan is a particularly painful illustration of the human suffering caused by the illegal dumping of wastes."

He warned that as global trade flows expand and tough domestic controls raise the costs of hazardous wastes disposal in developed countries, "the opportunities and incentives for illegal trafficking of wastes will continue to grow."

An inter-agency UN taskforce has been established to coordinate the response of UN agencies operating in the West African country.

Under the Basel Convention, any nation exporting hazardous waste must obtain prior written permission from the importing country, as well as a permit detailing the contents and destination of the waste. If the waste has been transferred illegally, the exporter is obliged to take back the waste and pay the costs of any damages and clean-up process.

European Union (EU) laws implementing the Basel Convention also prohibit all exports of toxic wastes from a member State to a developing country.

Copyright © 2006 UN News Service. All rights reserved. Distributed by AllAfrica Global Media (allAfrica.com).

http://allafrica.com/stories/200609080551.html

AlterNet:

911 Plus Five Equals...?

By Will Durst, AlterNet

Posted on September 8, 2006

Monday is the fifth anniversary of IX-XI, and President Bush has apparently decided to prepare us for our national day of mourning by delivering a weeklong series of seminars on fear mongering.

Okay, okay, maybe "fear mongering" is a bit much. Perhaps a better phrase would be "PR campaign of cheap political calculation," or "systematic exploitative pandering" or "a typical sleazy example from the Karl Rove electioneering handbook." Or as we have to come know it during the last six years: "business as usual."

First Dubya played the Nazi card, calling Democratic plans for a phased withdrawal of our forces from Iraq an appeasement similar to Chamberlain's treatment of Hitler in '39. I'm surprised he didn't unveil secret footage of Nancy Pelosi brandishing a rolled-up umbrella.

Then he played the Red Menace card, invoking Lenin and intimating a hammer and cycle tattoo on Howard Dean's forehead invisible only due to a thickly slapped on layer of "Dark Egyptian Number 4" makeup.

And if these two jackbooted images don't do the trick, expect to hear him summon up other more ancient scourges like the Huns and the Mongols and the Visigoths, in his never-ending quest to keep Americans all aquiver so we run and hide behind his urban camouflaged pants right up until the clock strikes 8pm PST, November 7, 2006. Screw Hawaii.

Uncharacteristically, Democrats refused to curl up in their customary flinching fetal position at the sound of the President's big bad rhetoric, and ratcheted up their criticism of his War policies, calling for the institutionalized bitch-slapping of Donald Rumsfeld in a transparently futile attempt to get the Secretary of Defense to join 10,000 Intel workers in next month's unemployment line. Predictable as a papier mache roof in a Category 3 Hurricane? Yes. But as they say about fire, it take politics to fight politics.

White House spokesman Tony Snow knee-slapped and guffawed and scoffed at the Democrats' proposal stating that portraying Rumsfeld as a bogeyman "may make for good politics but makes for lousy strategy." And one can't immediately discount that opine, because if anybody has experience with lousy strategies, it's this White House.

An administration that strategized the best way to stem terrorist activity was to invade a country that had none. An administration that stragetized that applying car battery contacts to a prisoner's nipples was not torture because it wasn't life threatening. An administration that stragetized that causing the death of over 100,000 non-combatant Iraqis was going to win over the hearts and minds of their countrymen. An administration that considers the best strategist to be the one who finds the biggest stick. Do the names Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld and John Bolton have any meaning here?

In just one of his series of deep-tissue massages of fear and loathing, Bush mentioned Osama bin Laden by name 18 times, conveniently neglecting to mention it was HE who DISBANDED the CIA division devoted to finding the 6'7" Arabian guy traipsing around the Kyhber Pass, dragging behind him a solar powered kidney dialysis machine from the islamabad Sharper Image Catalogue.

A long long time ago, in a galaxy far far away, the President spoke to the country of bin Laden: "He can run, but he can't hide." You know what, it's been five years. I think they're both hiding - one behind the billowing skirts of the other.

Comic, writer, actor, radio talk show host, burden to his family, Will Durst, after his vacation, doesn't need Dark Egyptian Number 4.

© 2006 Independent Media Institute. All rights reserved.

View this story online at:

http://www.alternet.org/story/41439/

Arab News:

Lessons of Lebanon and 9/11 Attacks

Dr. Khaled Batarfi, kbatarfi@al-madina.com

Sunday, 10, September, 2006 (17, Sha`ban, 1427)

What is the difference between a report and an Op-Ed piece? A reporter should cover all sides in his/her news story or analysis. A column, on the other hand, is meant to express a writer’s own opinion. At least this is my understanding. Obviously my American friend does not subscribe to this view or he does not recognize this vital difference. Hence his suggestion that I should be “fairer” in my articles about the Lebanon war. A journalist, he says, should represent all sides of a conflict, regardless of his or her own views.

I explained to him that I am not writing as a journalist, but as an opinion writer. Besides, Israel and company have powerful media forums whereas Arabs have very few. It is not fair to share the little space we have with Israeli apologists. Readers have greater access to the other side, so they won’t have a problem getting the Zionist message.

My friend insisted that at least I be logical, sensible and credible. For my opinion to be heard and respected by all sides, he argued, it has to show restraint, factuality and reason.

I agree. I must not lie or twist facts to support my stand or to convince my readers. Like a lawyer arguing a case, I could highlight certain facts and ignore others, knowing my opponent would focus on them, but abusing the truth is not permissible.

I should also be moral. For example, I must not preach hate, support injustice or advocate violence and terrorism. No moral writer can be anti-Semite, support Israel’s indiscriminate bombing of civilians in Lebanon or Palestine, or apologize for Al-Qaeda targeting civilians.

However, as long as I adhere to standard ethic rules, I am free to take any stand I feel right.

Anger, my friend contented, blurs reason. I should not write when I can’t control my emotions. He noted that my articles after the cease-fire in Lebanon were more like me than the ones I wrote during the war.

I told him that in the heat of conflict, sense and sensibility takes a back seat to anger, obstinacy and revenge. It is just hard for people under fire to think kindly of the shooters, or find excuses for their behavior. Shouts and war cries silence any fair reasoning and logical review. We are but humans.

However, after the battle storm dies down, sanity should rule. Now that Lebanon is on the road to recovery, we could afford to breath easier, think logical, and be fair even to our enemy.

We expected this from the world’s only superpower and leader, USA, soon after 9/11. Wounds were supposed to start healing, and forward, positive, scientific and constructive thinking was expected to take over. Emotional responses were the last thing anyone predicted. Yet, that is exactly what happened and still happening five years after the event.

Adventures like Iraq invasion justified with lies and truth-twisting backfired on the perpetrators. Supporting other criminal adventures like “bombing Lebanon to the Stone Age” and destroying Palestinian towns and villages drained whatever left of world sympathy toward America after 9/11, as international polls show.

In Afghanistan, Iraq and Lebanon, mostly innocent people and their homes and towns were destroyed. The bad guys are still at large, regrouping and attacking with the support of large portions of their societies. Victims are turned into avengers. Angry fellow brethren all over the Muslim world became a huge pool of potential jihadists against the occupiers. If only half a percentage of some 1.5 billion Muslims went down that road there would be multimillion fighters.

From Spain and UK to Indonesia and the Philippines, and from Morocco and Egypt to Saudi Arabia and Iraq, the terrorist attacks have increased many folds. Against all security preparations, terrorists managed to deal blow after blow to all of us. Evidently, the world is less safe today than it was before the war on terror.

Instead of stopping the bleeding, more blood, American included, was spilled all over, and enormous economic costs slowed the development of a better world. Worse, fear, hate and mistrust ruled a globe that was starting to be interconnected with instant and affordable communication, trade and education — a world that was starting to establish a new order based on the rule of law, justice and human rights.

Within months of 9/11, the dream we nurtured for half a century since the end of World War II evaporated with the first B52 bombing of villages and farms in poor Afghanistan. Instead of healing the wounds and uniting the world against preachers of hate and manufacturers of death, the theories of “The Clash of Civilization” and “The End of History” are now becoming more and more a reality.

In five years, we witnessed how the leaders and builders of the emerging free, peaceful world gradually turned into its jailers and destroyers. We deserved better!

Copyright: Arab News © 2003 All rights reserved.

http://www.arabnews.com/?page=7§ion=0&article=86334&d=10&m=9&y=2006

il manifesto:

I maestri dell'11 settembre

Come cominciò la guerra Cinque anni fa l'attacco al World Trade Center

Verità ambigue e oscure, curiose coincidenze che alla Casa bianca non piace siano indagate, intorno a degli strani fatti concomitanti con l'attacco terroristico al cuore di New York

Sergio Finardi

Terrore e «guerra al terrore» si tengono per mano ogniqualvolta la politica si avvicina a certi nodi o la tensione «securitaria» si abbassa. Anche l'ultimo «complotto» di Londra - quello che avrebbe dovuto far esplodere un sacco di aerei, il mese scorso - darà a Bush qualche argomento per cercare di fermare la caduta libera della sua popolarità in vista delle elezioni di mid-term; anche Blair sperava (a quanto pare senza successo) di ricavarne un sostegno contro gli attacchi della società civile e del suo stesso partito - che gli rimproverano, tra l'altro, la sua scelta di trasformare gli aeroporti inglesi in centri di smistamento di voli Cia e di voli civili/militari Usa carichi di armi dirette in Israele. All'indomani della scoperta del complotto, Bush e Blair hanno subito enfatizzato che la loro guerra al terrore è più che giustificata e dovrà essere anzi rafforzata. Che siano state e siano le loro politiche a provocare la deriva terroristica non viene naturalmente menzionato; men che meno il fatto che forse c'è più di un legame tra le due cose.

E' allora forse necessario tornare a riflettere su una delle origini principali della «guerra al terrore»: gli eventi dell'11 settembre 2001. La strada verso la verità si è fatta piu ampia e nuove cose sono emerse, anche grazie ad un determinato «movimento per la verità sull'11 settembre» che ha preso piede proprio negli Stati uniti e che, ad esempio, nel giugno di quest'anno ha organizzato due importanti assise: Los Angeles ha ospitato l'American Scholars Symposium «9/11 + Neo-Con Agenda» e Chicago l'annuale Conferenza del movimento per la verità sul 9/11, con il titolo «9/11: Rivelare la verità, rivendicare il nostro futuro».

Quante esercitazioni...

Si ricorderà che alcune esercitazioni e operazioni relative ad attacchi aerei e biologici sul suolo statunitense erano in corso l'11 settembre 2001, alcune di esse iniziate nei giorni immediatamente precedenti. Ognuna di tali esercitazioni implicherà conseguenze considerevoli sulla risposta agli eventi di quel giorno, non foss'altro per le gravi confusioni tra «esercitazione» e «realtà» che esse provocarono.

L'esistenza di tali esercitazioni è emersa dalle indagini svolte dagli studiosi del «movimento per la verità sull'11 settembre», dalla cosiddetta Commissione sul 9/11 (Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, 2004, testimonianze dei vertici militari, di Rudolf Giuliani, sindaco di New York, e altri passaggi), nonché su alcuni fonti di stampa (Toronto Star, 9 dicembre 2001; Associated Press, 21 Agosto 2002; Aviation Week & Space Technology, 3 Giugno 2002; Usa Today, 18 aprile 2004) e nel libro «Against All Enemies» (2004) di Richard Clarke, capo dell'antiterrorismo statunitense al tempo degli eventi e coordinatore con Cheney della «risposta» agli attacchi. In dichiarazioni ufficiali dei comandi militari si è parlato, senza ulteriori specificazioni, di un «maestro» coordinatore di quelle esercitazioni. Vediamone la sequenza temporale.

Il tempo di una di queste esercitazioni/operazioni (Operation Northern Vigilance) non venne deciso negli Stati uniti, poiché il suo scopo era di sperimentare le capacità di controllo dello spazio aereo nordamericano e di risposta militare in relazione ad una contemporanea esercitazione aerea militare russa sull'Artico e Pacifico settentrionale. L'esercitazione, annunciata il 9, venne condotta sotto la direzione del North American Aerospace Defense Command (Norad).

Il riflesso più immediato di tale operazione sugli eventi dell'11 fu che una buona parte dei caccia solitamente disponibili nelle basi della costa est a difesa di Washington e New York venne dislocata in basi dell'Alaska e del Canada settentrionale. Al momento dell'emergenza, il Norad aveva solo 8 caccia a disposizione nel settore orientale. Northern Vigilance venne interrotta la mattina dell'11 dopo il primo attacco al World Trade Center, quando i russi annunciarono di aver sospeso la loro per permettere agli statunitensi di focalizzarsi sull'emergenza.

Il tempo delle altre esercitazioni venne invece deciso da qualche entità interna agli Stati uniti: Global Guardian e Vigilant Guardian/Vigilant Warrior erano esercizi routinari effettuati sotto il comando militare, previsti solitamente per l'ottobre. Esse implicavano sia l'immissione sui sistemi della Federal Aviation Administration (che controlla il traffico aereo statunitense e partecipava all'esercitazione), di false informazioni indicanti il dirottamento di aerei civili, sia l'esecuzione di voli effettivi di aerei civili che dovevano agire come aerei dirottati (per testare le capacita di intercettamento). Le esercitazioni coinvolgevano in particolare un settore del Norad, il Neads (North-East Air Defense Sector), responsabile per la costa est. Le esercitazioni erano in corso durante gli attacchi e sono agli atti le frasi di alcuni controllori Faa che si chiedono se la sparizione dai radar di segnali che identificano alcuni aerei sotto il loro controllo fosse parte dell'esercitazione o fosse indicativa di eventi reali.

Nella stessa mattina dell'11 settembre, un'altra esercitazione, questa condotta da Cia e Nro (National Reconaissance Office, responsabile della gestione dei satelliti-spia statunitensi) coinvolgeva lo scenario di un aeroplano che fosse precipitato sul quartiere generale della Nro - situato a circa 6 km dall'aeroporto Washington-Dulles - con prove reali di evacuazione del personale, di cui c'è testimonianza ufficiale.

Infine, per la mattina del 12 settembre, l'Office of Emergency Management (Oem) che aveva sede nella torre Wtc7 fatta evacuare alle 9,30 dell'11, aveva previsto un'esercitazione civile contro un attacco biologico a New York City, in congiunzione con la Fema (Federal Emergency Management Agency) e il Dipartimento della giustizia. L'esercitazione, chiamata Tripod II, o Trial Point of Dispensing, aveva la sua sede operativa al molo 92, sull'Hudson. Quando la Wtc7 verrà evacuata, l'Oem si trasferirà alla sede di Tripod II (testimonianza di Rudolf Giuliani alla National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States, vedi www.gpoaccess.gov/911).

Né la grande stampa ha mai chiesto, né le commissioni ufficiali sugli avvenimenti dell'11 settembre e i comandi militari hanno mai voluto dire chi fosse il «maestro» di quelle esercitazioni, ovvero il loro punto di pianificazione e coordinamento. Il 16 febbraio 2005, in un'udienza della Camera dedicata alle allocazioni di bilancio per la difesa, la deputata Chinthia McKinney chiese al ministro della difesa Rumsfeld di dare informazioni su quelle esercitazioni. Non ottenne alcuna risposta perché il presidente della sessione non consentì altro che quella domanda fosse messa semplicemente a verbale per future sessioni.

Tuttavia, non tutto è oscuro sul «maestro»: un comunicato stampa della Casa bianca dell'8 maggio 2001, quattro mesi prima degli attentati, recita: «Il presidente Bush ha ordinato al vicepresidente Cheney di coordinare lo sviluppo delle iniziative del governo per combattere attacchi terroristici sul suolo degli Stati uniti». (Office of Press Secretary, the White House). Entro il quadro della preparazione per combattere «attacchi terroristici» ricadeva anche il coordinamento e la supervisione dei cosiddetti war games e di uno speciale ufficio, l'Office of National Preparedness (Onp), istituito con la stessa direttiva dell'8 maggio nell'ambito della Fema, il cui direttore, Joe Allbaugh, da allora risponderà direttamente a Cheney delle attività dell'Onp.

Il nuovo nemico

Molti anni prima, nell'estate del 1993, il politologo statunitense Samuel Huntington pubblicherà su Foreign Affairs, organo del Council for Foreign Relations di rockefelleriana moneta, il suo famoso saggio Clash of Civilizations? I poteri forti che dominano la politica statunitense, troveranno in quel saggio il nuovo Graal, la teoria che avrebbe sostituito quella del nemico totale sovietico: le braci dei conflitti etnici e di religione sarebbero tornate ad ardere, con l'aiuto di fanatici che abbondano in ogni parte del globo, Stati uniti inclusi. Non era, quella di Huntington, un'analisi scientifica sui nuovi pericoli del mondo, ma il suggerimento di un programma di intervento.

Nel 1997, l'ex-consigliere alla Sicurezza nazionale Zbigniew Brzezinski avrebbe scritto nel suo libro La grande schacchiera: l'egemonia americana e i suoi imperativi: «Nel tempo in cui l'America diviene una società sempre più multiculturale, si può trovare sempre maggiore difficoltà a costruire un consenso sui temi della politica estera, eccetto che nella circostanza di una massiccia, universalmente sentita, e diretta minaccia esterna». Come è noto, l'amministrazione Bush si opporrà per più di un anno alla formazione di una commissione d'inchiesta sugli eventi dell'11 settembre, formata solo il 27 novembre 2002 e durata quasi due anni, non ultimo per l'opposizione continua apposta dalla Casa bianca al rilascio dei documenti richiesti dalla commissione, la più parte dei quali non verrà mai desecretata.

Dagli war games alle guerre vere i passi sono stati brevi e le loro ombre lunghe si stendono oggi da Tel Aviv a Beirut, da Baghdad a Kabul, da Washington a Bruxelles.

http://www.ilmanifesto.it/Quotidiano-archivio/09-Settembre-2006/art11.html

il manifesto:

Novecento, il dubbio degli sconfitti

«Volevo la luna», ardenti vicende e tormentati ricordi che intrecciano la storia personale con l'esperienza collettiva del comunismo italiano. L'autobiografia di un protagonista della politica italiana «Noi siamo stati sconfitti, ma abbiamo vissuto un'esperienza straordinaria. Oggi, a volte, l'orizzonte della politica mi sembra diventato più piccolo e angusto»

Gabriele Polo

Guardarsi alle spalle per riflettere su una vita intensamente politica, per raccontare le virtù di un mondo ma soprattutto e impietosamente i suoi «peccati», gli errori. In una confessione pubblica che non cerca assoluzioni ma ragioni. Pietro Ingrao manda in libreria Volevo la luna (Einaudi, pp. 376, euro 18,50) più che un'autobiografia un percorso di ricerca in cui racconta se stesso «come parte di un soggetto che si sentiva protagonista del mondo e del suo cambiamento». Il soggetto è il movimento comunista - meglio, il comunismo italiano - che è il centro di tutta la narrazione. Con i suoi problemi aperti.

Il ripensamento autocritico è il filo conduttore di tutto il libro.

Cosa hai voluto trasmettere con questo tuo lavoro?

La sensazione molto netta di una sconfitta di cui mi convinco alla fine degli anni Settanta, con la necessità di ragionare a fondo sulla nostra storia e sulla realtà, per riaggiornare le nostre categorie e riflettere sul soggetto politico. Dovevamo ridisegnare le nostre «mappe».

Vuoi dire che soltanto nelle sconfitte si può arrivare a scorgere le verità e a poterle dichiarare?

E' un'affermazione troppo secca, anche se forse per alcuni è così. Per me c'era il farsi strada della convinzione netta di una sconfitta concreta e drammatica. Pensa a che colpo fu per noi l'occupazione sovietica di Praga del 1968 che poneva fine a un tentativo di rinnovamento democratico del socialismo che noi in Italia sostenevamo. Tutto il nostro mondo era in subbuglio da tempo e noi eravamo un po' fermi nell'elaborazione. Con il '68-69, soprattutto in Italia, viene messo in discussione il concetto di rappresentanza - per quanto riguarda il sindacato nei metalmeccanici il processo è addirittura travolgente - e da lì sorge in me una domanda che riguarda l'agire politico in generale. Non solo cosa fa il Partito comunista italiano o cos'è l'Unione sovietica, ma proprio che cos'è la politica, più nel profondo la convinzione che il soggetto rivoluzionario sia, come scrivo nel libro, «un farsi del molteplice, l'incontro fluttuante di una pluralità oppressa che costruiva e verificava nella lotta il suo volto». E' qualcosa di più di una critica da sinistra dello stalinismo.

Il '68-69 sembrava essere una grande occasione che non annunciava nessuna sconfitta, anzi. Perché questa «occasione» non è stata colta dal Pci e, per esempio, non ti ha impedito di commettere - le parole sono le tue - un errore grave come la radiazione del gruppo del manifesto? Perché ha prevalso il primato della fedeltà all'organizzazione?

Perché io non credo al minoritarismo. Con i compagni del manifesto c'era e c'è sempre stato un grande rapporto di solidarietà e amicizia, ma mi è parso che non ci fosse da parte loro una proposta valida sul tema del soggetto politico. Mi ricordo le discussioni con loro. Io conoscevo bene il Pci e avevo detto a loro: «Vi mettono fuori». Ma entrando più nel merito non trovavo in quella che facevano una proposta chiara sul soggetto da mettere in campo. Purtroppo, per parte mia, commisi l'errore pesante e assurdo di votare la loro radiazione. Questo limite nella costruzione di un nuovo soggetto poltico l'ho poi ritrovata in voi del manifesto, compresa l'esperienza che ho vissuto nella Rivista degli anni '90. Un minoritarisimo di testimonianza che non mi ha mai persuaso.

Quindi la tua autocritica è essenzialmente etica, come di fronte a un peccato...

No, non faccio valutazioni morali. Fu un doppio errore, il mio. Il primo senza dubbio umano, abbandonavo i miei amici. Soprattutto la radiazione fu una scelta politicamente stupida, non apriva una discussione positiva, non faceva avanzare la coscienza comune valutando e comprendendo le ragioni del dissenso in campo.

Però allora ci fu una grande discussione nel Partito comunista, in tutte le federazioni, gli atti furono pubblicati...

Ma era già tutto stabilito dall'inizio, quella discussione fu solo una formalizzazione di una decisione già presa. Invece bisognava usare quella frattura per misurarsi con la crisi del leninismo. Tale era il nodo da affrontare.

A proposito di leninismo, sempre nel passaggio sul manifesto, tu parli di fare i conti «con il suo doloroso tramonto». Quel «doloroso» sembra quasi un lamento, come a dire che bisogna ammettere quel fallimento ma che si è in presenza di un'assenza di alternative, di fronte a un vuoto.

Dire che non c'era alternativa è troppo povero e alla fine inutile: ma sicuramente il cibo di cui ci eravamo nutriti non era più utilizzabile. Tutti sapevamo che nell'Urss non c'erano più interlocutori. Ma il vuoto di cui tu parli è più forte proprio in assenza di una riflessione sulla necessità di creare un nuovo soggetto che sia frutto della «molteplicità» di cui parlavo prima.

Il «molteplice» prevede un grande senso della democrazia non solo come serie di regole da rispettare, ma soprattutto come pratica, a partire dal rispetto del dissenso. Era proprio così impossibile, prima degli anni '70, permettere la manifestazione del dissenso fuori da ristretti gruppi dirigenti?

Di fatto è stato così. Chi dissentiva la pagava duramente, fino a metodi polizieschi, soprattutto nella vecchia guardia. Come scrivo nel mio libro erano tempi difficili...

Tempi difficili ma molto «pieni». Oggi magari sono più facili ma forse ti appaiono più «vuoti».

La domanda è provocatoria perché si potrebbe accusare un vecchio come me di nostalgia per la sua gioventù. Io però non voglio cancellare un grande fatto che ha segnato l'Italia: noi siamo stati sconfitti, ma abbiamo vissuto una stagione straordinaria, che ha fatto crescere un'esperienza di milioni di persone che hanno fatto politica cambiando il paese, democratizzandolo. E, poi, il nostro orizzonte non guardava solo all'Italia: eravamo parte di un «mondo» e di una pratica collettiva alta e vitale in tante parti del pianeta. Quando sono andato in Vietnam e sono sceso nelle città sotterranee costruite per sfuggire ai bombardamenti americani, io in quei cunicoli bui divisi da muri di fango mi sentivo in uno spazio aperto e illuminato da una lotta creativa. Oggi, a volte, l'orizzonte della politica mi sembra diventato più piccolo e angusto.

Ma allora il tuo dirti comunista ancor oggi, nonostante la sconfitta, gli errori e le autocritiche, è legato più a questo passato che all'oggi?

Noi - quelli della mia generazione - non siamo riusciti a trovare la risposta alla crisi indiscutibile del leninismo-stalinismo. E, prima di tutto per questo, siamo degli sconfitti. Però, da un lato in questo paese ci sono state milioni di persone che sono cresciute anche culturalmente nella lotta politica e che sono state una parte decisiva dell'esperienza democratica italiana; d'altro canto oggi continuo a vedere milioni di oppressi nei drammatici mutamenti della globalizzazione. E, poi, vediamo il riemergere apologetico della guerra come realtà pressante e distruttiva che dilaga nel mondo, mentre è stata cancellata dal vocabolario la parola disarmo: non c'è più nessuno che la pronunci, nemmeno voi sul manifesto. Non ti sembrano buoni motivi per continuare a dirsi comunisti e a lavorare per la costruzione di un soggetto politico su scala necessariamente internazionale?

Scusa la digressione: tu hai ammesso nel tuo libro gli errori che hai fatto rispetto al gruppo del manifesto. Quali errori commette oggi il manifesto nei confronti dei suoi lettori e della sinistra?

Ma perché mi fai questa domanda?

Perché ci interessa l'opinione di un lettore importante che è stato anche direttore di un giornale politico.

Va bene. Allora diciamo che a volte - scusa l'impertinenza - sembrate una setta aristocratica. E lo dico con tutto l'affetto possibile e l'interesse per quello che scrivete.

Torniamo al libro, al suo titolo, «Volevo la luna». La senti più lontana o più vicina di un tempo quella luna, metafora di un mondo diverso?

Ti ripeto che questo è un libro che racconta una sconfitta...

Ma non pensi che questa tua ricerca lunga una vita sia stata in qualche modo utile e fruttuosa?

Per gli altri non spetta a me dire. Per me sicuramente è stata utile e fruttuosa. La passione politica mi ha fatto capire il mondo ed è diventata un pane necessario. La «luna» mi sembra ora un po' più distante: non rispetto all'inizio del mio percorso, ma negli ultimi anni mi pare essersi un pochino allontanata. Io sono arrivato alla politica sotto la spinta di una necessità. Come tanti altri della mia generazione e della mia estrazione sociale avrei voluto fare altre cose - il cinema, per esempio. Poi sono stato spinto dagli eventi, a calci nel sedere; e la guerra civile spagnola è stato il momento di passaggio che mi ha trascinato nella lotta politica. Da lì è cominciato un cammino che mi ha riempito di cose straordinarie, che mi ha fatto uscire dal guscio dell'individualismo entrando in comunicazione con milioni di esseri umani. Questa è stata l'esperienza dei comunisti italiani. Però è andata in crisi la forma che ha storicamente assunto il soggetto politico. Questo oggi mi sembra pesante, persino doloroso, perché non vedo una risposta all'altezza degli eventi che sono maturati. La mia generazione ha pagato il prezzo di una forma restrittiva della molteplicità (ricordi il mio discorso di prima?) dell'attore politico. Qui è l'enorme, straordinario campo dell'innovazione. Il senso del mio libro, alla fine, si riduce tutto nel fornire il mio piccolo ragionamento per questa grande e nuova ricerca.

http://www.ilmanifesto.it/Quotidiano-archivio/09-Settembre-2006/art43.html

Jeune Afrique:

La Corne et le Coran

SOMALIE - 3 septembre 2006 - par CHERIF OUAZANI

Le phénomène islamiste réveille les rancœurs tribales. Dans la sous-région, certains s’en inquiètent. D’autres tentent d’en tirer profit.

Depuis le 26 mai, date à laquelle les fondamentalistes de l’Union des tribunaux islamiques ont fait main basse sur Mogadiscio, la Corne de l’Afrique est entrée dans une zone de fortes turbulences. À leurs conquêtes militaires, les islamistes ont ajouté, en quelques semaines, des performances économiques qui accroissent leur popularité auprès des Somaliens : réouverture de l’aéroport et du port de Mogadiscio fermés depuis plus de dix ans, sécurisation des activités de pêche, recul de la criminalité dans les zones sous leur contrôle, etc. Les intégristes se sont si bien assurés du soutien de la société civile, d’hommes d’affaires et d’une partie de la diaspora que leur influence commence sérieusement à inquiéter. Dans les pays voisins… et au-delà.

La Somalie est un pays sans État depuis la chute, en 1991, du dictateur Mohamed Siyad Barré. La brusque disparition du maître de Mogadiscio avait alors réveillé les rancœurs tribales et les ambitions claniques. Une intervention américaine avait bien tenté de ramener le calme dans le pays, mais la mémorable opération Restore Hope, en 1993, s’était soldée par un fiasco. Depuis, de longues batailles à l’arme lourde entre seigneurs de guerre ont achevé de mettre le pays à genoux, sans que les Nations unies ne parviennent à y rétablir la paix.

En 2004 pourtant, après de multiples médiations infructueuses, le Parlement institué en 2000 choisit l’un des seigneurs de guerre, Abdallah Youssouf Ahmed, l’homme fort du Puntland, comme président. Ahmed Gédi dirige un gouvernement en exil au Kenya. Mais celui-ci ne parvient pas à enrayer la montée de l’islamisme radical qui atteint la Somalie.

Le 15 juin dernier, l’Union des tribunaux islamistes accepte quand même de signer, à Khartoum, un mémorandum de reconnaissance mutuelle avec le gouvernement d’Ahmed Gédi. Mais les négociations ne vont pas plus loin. Les deux parties ne parviennent pas à se mettre d’accord sur les modalités du retour à la paix. Pour les intégristes, il n’est pas question d’accepter la présence en Somalie de militaires étrangers, fussent-ils arabes et musulmans, envoyés dans le cadre d’une mission de maintien de la paix. Le président Abdallah Youssouf campe, lui, sur ses positions : « Cette disposition est inscrite sur les tablettes de l’Union africaine (UA). Refuser sa mise en œuvre équivaut à remettre en cause notre légitimité. » Le différend menaçant de sortir du seul cadre verbal, le président Youssouf et son Premier ministre décident de faire appel à l’Éthiopie, aujourd’hui soupçonnée d’avoir envoyé des troupes en Somalie. Addis-Abeba dément. Mais les témoins soutiennent que près de 25 000 soldats éthiopiens sont entrés sur le territoire somalien pour prêter main forte aux milices progouvernementales à Baidoa.

La nouvelle provoque la colère des islamistes. « Haute trahison ! » s’écrie Hassan Dahir Awess, leur leader, recherché par la justice américaine pour ses accointances avec al-Qaïda. La présence d’un corps expéditionnaire éthiopien, donc chrétien, en terre somalienne est ressentie comme une croisade. L’Union des tribunaux islamiques rédige alors une fatwa appelant au djihad contre l’envahisseur.

L’Union africaine, dont le siège se trouve dans la capitale éthiopienne, reste discrète. Et se cache derrière l’Autorité intergouvernementale pour le développement (Igad), l’organisation sous-régionale en charge du dossier somalien. Le 1er août, un Conseil des ministres de l’Igad se tient à Nairobi, le Kenya assurant la présidence tournante de la structure qui regroupe Djibouti, l’Éthiopie, l’Érythrée, le Kenya, l’Ouganda et le Soudan. L’Igad réitère son soutien aux institutions de transition et appelle à un dialogue entre le gouvernement d’Ahmed Gédi et les fondamentalistes, dans le cadre de la charte fédérale de transition, qui prévoit le déploiement d’une force africaine d’interposition. Mais les discussions piétinent faisant croître l’inquiétude dans la région.

L’Éthiopie, en particulier, est dans l’urgence. Pour elle, il est vital de mettre fin à la percée islamiste en Somalie au plus vite. Le succès des fondamentalistes somaliens risque d’être contagieux et pourrait apporter des soutiens mal venus aux insurgés du Front de libération oromo, proche des islamistes. En outre, une Somalie stable avec, à sa tête, un pouvoir hostile à Addis-Abeba est la porte ouverte au retour d’une vieille revendication : la Somalie doit regrouper toutes les régions où l’on parle somali. Soit de Djibouti au nord du Kenya, en passant par le plateau de l’Ogaden et une partie de l’Éthiopie orientale...

Quant à l’Érythrée, toujours en conflit larvé avec Addis-Abeba malgré l’accord de paix d’Alger de 2000, elle ne rate jamais l’occasion de mettre des bâtons dans les roues de son puissant voisin. Selon différentes sources, c’est elle qui alimente les combattants islamistes somaliens en armes et en munitions. Certaines évoquent même la présence de 1 500 militaires érythréens, venus par la mer, aux côtés des miliciens de l’Union des tribunaux islamiques. Difficile à croire quand on sait que les côtes somaliennes sont étroitement surveillées par une coalition sous commandement américain, installée au camp Lemonier de Djibouti. Toujours est-il que l’intrusion de l’Érythrée dans le dossier ajoute à la confusion. D’autant que pour les Nations unies, la question somalienne relève exclusivement de l’UA, qui, elle-même, la sous-traite à l’Igad. Une situation complexe qui profite, pour l’instant, aux intégristes de Hassan Dahir Awess. Après avoir consolidé leur assise militaire, ces derniers réhabilitent actuellement les infrastructures du pays. Le risque ? Voir une Somalie en jachère se transformer en un Afghanistan taliban...

© Jeuneafrique.com 2006

http://www.jeuneafrique.com/jeune_afrique/article_jeune_afrique.asp?

art_cle=LIN03096lacornaroce0

Página/12:

Ground Zero, imposible de olvidar

MAÑANA SE CUMPLEN CINCO AÑOS DE LOS ATAQUES A LAS TORRES

Cinco años después, la huella del 11-S se observa en peleas políticas, en nuevas investigaciones y en grabaciones de rescate de emergencias recientemente dadas a conocer. Pero sobre todo se siente al pie de donde alguna vez se alzaron dos torres.

Por David Osborne*

Desde Nueva York, Domingo, 10 de Septiembre de 2006

Habrá más movimiento esta semana en Ground Zero, donde alguna vez estuvieron las Torres Gemelas. Con motivo del quinto aniversario de los ataques terroristas del 11 de septiembre, está llegando más gente que la habitual al pozo gris y estudia las fotografías del horror que están pegadas al cerco. Hoy en día es un lugar estéril. Nueva York se tomó todo este tiempo para dilucidar los conflictos de intereses que rodean a los planes para la nueva Torre de la Libertad, el Museo de la Memoria y diversas oficinas, negocios minoristas y edificios culturales. Las peleas sobre el dinero del seguro, las normas de seguridad para las nuevas estructuras y sobre lo que las familias de las víctimas consideran apropiado para su suelo sagrado, casi han terminado, y finalmente se están excavando algunos cimientos. Pero Ground Zero sigue provocando fuertes emociones.

Apártense de esta herida y rápidamente llegarán a la conclusión de que Nueva York se corrió de la masacre que sufrió con indecorosa rapidez. De vuelta está la antigua ciudad arrogante, alimentada por un nuevo boom económico. Unos amigos acaban de comprar un departamento frente a la Bolsa de Comercio, uniéndose a la corrida, que está ocurriendo en todo Manhattan, por nuevas moradas lujosas en edificios de oficinas reciclados. Que vayan a estar durmiendo a unas cuadras de Ground Zero no es ya un problema. Es un área de onda para vivir, o lo será.

Querer olvidar es normal, aun si uno es alguien que sufrió personalmente por los ataques –quizás especialmente para ellos–. Cuando comenzamos el trabajo de entrevistar a los familiares de las víctimas para este informe del aniversario, para lograr una mirada sobre cómo habían reparado sus vidas, nos encontramos que muchos ya no estaban dispuestos a participar. Una mujer que había perdido a su padre acababa de dar a luz a su primer bebé. Un trabajador de rescate acababa de comenzar una nueva vida en Oklahoma. Ninguno estaba listo para revivir el dolor.

Sin embargo, olvidar no siempre es fácil, ni tampoco lo es desviar la mirada. Los recordatorios están por todos lados, a veces ocultos debajo de una carpa blanca del FDR Drive al lado del East River o detrás del lienzo negro que tapa la fachada de un viejo edificio bancario. Cinco años después, la confusión provocada por el 11-S está lejos de estar terminada, ya sea que se exprese en peleas políticas o en nuevas investigaciones o en grabaciones de rescate de emergencias recientemente dadas a conocer. Si no es por esto, estamos atacados por cosas del 11-S en el arte, incluyendo películas de Hollywood, o historias de los medios acerca de las viudas de los bomberos que encuentran el amor con otros bomberos.

Hasta yo prefiero no ver, aun cuando mi dolor fue meramente el de ver personalmente cómo se hundían las torres. Vi una película este verano, United 93. Peor, fui a una première en un cine lleno de parientes de pasajeros muertos. No fue una noche fácil. Las grabaciones dadas a conocer recién el mes pasado de despachantes hablando desesperados con personal de rescate y de oficinistas atrapados también eran demasiado duras de oír. Aquí hay un operador telefónico de emergencia tratando de tranquilizar a Melisssa Doi, una gerenta financiera, después de que su torre fuera impactada. Ella estaba en el piso 83. Operador: “Melissa... ¿no? Voy a llamar a tu mamá cuando salgas, que venga y vea cómo estás... Ey, ¿Melissa? Oh, mi Dios... Melissa, no te rindas. Por favor, por favor, no te rindas, Melissa. No te rindas. Oh, mi Dios. Melissa, Melissa, Melissa. ¿Querés que llame a tu mamá por vos y le diga que aguante? (Comienza el tono de discado.) “Oh, Melissa.”

Recién hoy nos estamos dando cuenta del alcance del daño hecho a la salud, física y mental, de los neoyorquinos. Un estudio conocido hace dos semanas sugiere que uno de cada seis de aquellos equipos de limpieza tiene ahora una depresión. El número de llamadas a la línea de salud mental de la ciudad se duplicó en la semana posterior a los ataques y todavía mantiene ese elevado número. El jueves pasado, la ciudad publicó por primera vez guías para diagnosticar las enfermedades físicas relacionadas directamente con el 11-S. “Cinco años después de los ataques al World Trade Center, muchos neoyorquinos tienen condiciones de salud físicas y mentales asociadas al desastre”, reconoció el comisionado de salud de la ciudad, Thomas Frieden.

Aun nuestras actitudes hacia aquellos directamente afectados por el dolor –las mujeres, maridos y niños de las víctimas– son fluctuantes. Anne Coulter, la escritora de opinión de derecha, hizo nuevos amigos este año cuando evaluó que algunas viudas del 11-S estaban “obsesionadas” y “disfrutando de las muertes de sus maridos”. Un pequeño núcleo de los parientes de las víctimas tomaron la delantera para hacer lobby ante el gobierno sobre una serie de temas posataques, incluyendo enmendar y demorar los proyectos para el nuevo World Trade Center. Pero puede ser que Coulter estuviera canalizando los celos públicos ocultos sobre el dinero que habían recibido –hasta 1,5 millón de dólares por viuda de bombero de los fondos de la compensación federal–.

La envidia por el dinero seguramente también está detrás de las historias que aparecen ocasionalmente en los periódicos sobre los bomberos que abandonan a sus mujeres por las viudas de sus ex colegas. Y está el caso de la estrella de rock Bruce Springsteen, que la semana pasada se encontró negando informes de que se separaba de su mujer Patti para unirse a una viuda de un bombero del 11 de septiembre.

Pero para entender totalmente por qué no se llegó al cierre cinco años después, uno necesita no sólo mirar el edificio tapizado de negro y la carpa. El primero es la ex torre del Deutsche Bank, un edificio de 43 pisos al lado de Ground Zero que todavía está esperando ser demolido. Aún está en pie por lo que hay adentro: pedazos de avión y, lamentablemente, de restos humanos. Este año, trabajadores con buzos antiflama y con máscaras para respirar han recuperado no menos de 750 restos individuales de víctimas del ataque, lanzadas al banco por el impacto de los aviones. Es a la carpa en la calle 30 y la Primera Avenida a donde se llevan estas nuevas evidencias de atrocidad.

Llamada Memorial Park, la carpa protege tres camiones contenedores controlados climáticamente, dentro de los cuales hay 13.790 restos de las víctimas de las Torres Gemelas. Están esperando la nueva tecnología de ADN que un día pueda permitir que los científicos unan definitivamente cada uno de ellos a los nombres de las víctimas que murieron. Eso puede llevar un largo tiempo, y antes de eso serán transferidas al Memoria en el mismo Ground Zero cuando finalmente sea construido. Estos restos son el testimonio de –quizá– la parte más triste y más frustrante del tema inconcluso del 11-S. Hasta ahora, los médicos examinadores han identificado sólo a 1598 víctimas, dejando a 1151 personas todavía sin reconocer en Ground Zero. Y eso ha dejado a 1151 familias sin restos para honrar y enterrar.

* De The Independent de Gran Bretaña. Especial para Página/12.

Traducción: Celita Doyhambéhère.

© 2000-2006 www.pagina12.com.ar|República Argentina|Todos los Derechos Reservados

http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/elmundo/4-72795-2006-09-10.html

Página/12:

Nein al antiterrorismo de Bush

MERKEL CRITICO LAS CARCELES SECRETAS DE LA CIA

Domingo, 10 de Septiembre de 2006

“El fin no justifica los medios en la lucha contra el terrorismo”, afirmó ayer la canciller alemana Angela Merkel, al condenar las cárceles secretas de la CIA. La existencia de esos establecimientos fue admitida esta semana por el presidente estadounidense, George W. Bush, en un discurso en la Casa Blanca. Merkel se sumó así a las críticas europeas contra las cárceles. “El empleo de esas prisiones no está en acuerdo con mi idea de estado de derecho”, agregó la canciller alemana.

Bush reconoció el miércoles, por primera vez, la existencia de prisiones secretas de la CIA en varias partes del mundo, donde fueron interrogados presuntos responsables de los atentados del 11 de septiembre de 2001, y pidió al Congreso que autorice a los agentes a interrogar a terroristas sin las ataduras de la Convención de Ginebra. El presidente norteamericano dijo que tras los atentados contra las Torres Gemelas y el Pentágono, un pequeño número de presos de la red Al Qaida fueron detenidos e interrogados fuera de Estados Unidos en un programa separado operado por la CIA. “Ha sido necesario trasladar a estas personas a un lugar donde fueran mantenidas en secreto, y pudieran ser interrogadas por expertos”, dijo Bush.

La admisión del presidente estadounidense generó inmediatamente una ola de críticas por parte de la Unión Europea (UE). “Ser aliado de Washington no significa automáticamente estar alineado”, dijo Nicolás Sarkozy, ministro del Interior francés, en una entrevista que publicó ayer el diario Le Monde. “En ningún caso y por ninguna razón Europa debe estar sujeta por Estados Unidos”, agregó el ministro. Las críticas de París se suman a las del presidente del gobierno español, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. “La lucha contra el terrorismo sólo puede hacerse desde los principios del estado de derecho y de la democracia. Eso no es compatible con la existencia de prisiones secretas o de métodos que no están dentro de lo que representan los elementos clásicos del estado de derecho y garantías para todos, incluso para presuntos terroristas”, indicó Zapatero.

Otros funcionarios también criticaron las cárceles secretas. “La lucha contra el terrorismo no puede hacerse con ataques al respeto de los derechos humanos y la protección de las libertades civiles”, dijo el secretario general de la ONU, Kofi Annan. El presidente de la Asamblea Parlamentaria del Consejo de Europa, René van der Linden, denunció por su parte que “la guerra sucia contra el terrorismo está fuera de la legalidad” y precisó que los métodos utilizados “a largo plazo, hacen el mundo más inseguro, no más seguro”.

© 2000-2006 www.pagina12.com.ar|República Argentina|Todos los Derechos Reservados

http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/elmundo/4-72796-2006-09-10.html

Página/12: Furor en Israel contra Olmert

por el levantamiento del bloqueo de Líbano

Los familiares de los dos soldados secuestrados se sumaron al ejército israelí en criticar la decisión del primer ministro. Le objetan que haya perdido una herramienta de presión contra Hezbolá.

Por Sergio Rotbart

Desde Tel Aviv, Domingo, 10 de Septiembre de 2006

Israel levantó el bloqueo aéreo y marítimo sobre el Líbano que había impuesto desde el pasado 12 de julio, cuando comenzó la guerra librada en ese país entre el ejército israelí y la milicia armada del Hezbolá. A través de esta medida, destinada a aliviar la presión ejercida sobre el gobierno libanés de Fouad Siniora, el premier Ehud Olmert accedió al reclamo de la administración norteamericana y del titular de la ONU, Kofi Annan. Pero, por otro lado, el desmantelamiento del control militar israelí sobre los accesos por aire y por mar al Líbano despertó no pocos cuestionamientos en Israel. En primer lugar, reaccionaron airadamente los familiares de Ehud Goldwaser y Eldad Regev, los soldados secuestrados por el Hezbolá en la frontera norte, quienes expresaron su disgusto al saber que la “concesión” del gobierno no estuvo condicionada por la aceptación de algún indicio positivo respecto del destino de los dos israelíes capturados. Su secuestro, que –según la versión oficial israelí– fue la causa de la ofensiva militar desplegada en el territorio libanés, sigue siendo un asunto irresuelto luego del cese de fuego y la parcial retirada del ejército.

“No creo que el objetivo de esta guerra haya sido conseguir la liberación de nuestros hijos”, dijo Mo-shé Goldwaser, padre de Ehud, uno de los soldados secuestrados por el Hezbolá. En un encuentro con el primer ministro Olmert, los familiares de los dos israelíes que –según se estima– aún se encuentran cautivos en manos de la organización chiíta, le expresaron su decepción ante la decisión de aceptar levantar el bloqueo al Líbano antes de haber obtenido algún avance orientado hacia la liberación de sus seres queridos. Tras la reunión, Goldwaser aclaró su posición: “No es posible que esta medida se cumpla solamente en una dirección. Nosotros exigimos del gobierno que actúe con rapidez para hallar un mediador que inicie negociaciones directas con la organización Hezbolá. Ello exigirá un pago, y nosotros reclamamos que, en el marco de un acuerdo, el gobierno acepte liberar prisioneros libaneses”.

El gobierno aprobó el levantamiento del bloqueo aéreo y marítimo sobre el Líbano, pese a las recomendaciones del ejército que, en cambio, sostenía que hubiese sido preferible mantenerlo como instrumento de presión ante el Líbano y la comunidad internacional destinado a mejorar los términos de un posible acuerdo sobre el intercambio de prisioneros y un control más riguroso del contrabando de armas desde Siria al territorio libanés. En ese sentido se pronunció días atrás Dan Halutz, el jefe del ejército, quien afirmó que el desmantelamiento del bloqueo “es una carta que hay que saber cuando poner sobre la mesa”. Una vez usada por el gobierno de Olmert, tal vez la retirada total de los efectivos militares del sur del Líbano sea la carta que le queda para conseguir un avance en dirección a la devolución de los soldados secuestrados y la disposición de las fuerzas internacionales a controlar la frontera entre el Líbano y Siria, el enorme acceso terrestre para el abastecimiento de armas al Hezbolá.

El gobierno ha desmentido, hasta ahora, las versiones sobre la existencia de negociaciones paralelas en torno de la liberación de los dos israelíes secuestrados por el Hezbolá y de Gilad Shalit, el soldado capturado por un grupo palestino en la frontera sur, lindante con la Franja de Gaza. En cambio, Olmert ha declarado que Israel exige su devolución previa a cualquier discusión acerca de la liberación de prisioneros libaneses y palestinos. De hecho, una vez que el principio de la reciprocidad ha sido reclamado por los propios familiares de los soldados cautivos, ningún vocero oficial puede asegurar que el declamado retorno se conseguirá sin la simultánea liberación de prisioneros que Israel retiene en sus cárceles. Quizá, para intentar restaurar algo de su dañada imagen pública, el gobierno ceda a las demandas de las contrapartes libanesa y palestina devolviéndoles a sus compatriotas detenidos en forma gradual.

Esa mínima muestra de reciprocidad, por cierto, bastaría para darle curso a alguna iniciativa negociadora en el plano más amplio del conflicto regional. La semana pasada, y no por primera vez, veintidós cancilleres de la Liga Arabe convinieron en la necesidad de convocar a una nueva conferencia internacional de paz como la celebrada en Madrid en 1991, la cual le dio impulso a las conversaciones entre israelíes y palestinos que condujeron al Acuerdo de Oslo.

Un decisión similar adoptó cuatro años atrás la cumbre árabe que tuvo lugar en Beirut, basada en una iniciativa de Arabia Saudita. Ella contemplaba la normalización de las relaciones entre los países árabes y el Estado de Israel a cambio de una retirada israelí de Cisjordania y Gaza, de acuerdo con los límites de 1967, donde se crearía un Estado palestino independiente. Israel, entonces, se desentendió de la propuesta, argumentando que la inclusión del tema del retorno de los refugiados palestinos y la partición de Jerusalén no daban espacio a ninguna respuesta positiva. El actual pedido de tratar el tema del proceso de paz será presentado por el bloque de países árabes con respresentación en la ONU, en la reunión que el Consejo de Seguridad del organismo realizará el próximo 23 de septiembre.

© 2000-2006 www.pagina12.com.ar|República Argentina|Todos los Derechos Reservados

http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/elmundo/4-72797-2006-09-10.html

Página/12:

La segunda vida de Jack

COMO CONSTRUIR UN FUTURO DESPUES DE AUSCHWITZ.

MEMORIAS DE UN SOBREVIVIENTE

“No soy ningún héroe, lo único es que no tenía el coraje de matarme.” Jack Fuchs habla de sí mismo sin concesiones. Durante cuarenta años prefirió callar sobre el infierno que había debido atravesar: el gueto, Auschwitz, el exterminio de toda su familia. Viajó por el mundo con una inquietud que le impedía afincarse. Hasta que un día pudo asentarse y también contar.

Por Andrea Ferrari

Domingo, 10 de Septiembre de 2006

La segunda vida de Jack Fuchs empezó en un galpón. Hasta allí había llegado con sus últimas fuerzas, luego de que el vagón donde los alemanes lo trasladaban junto con otros sobrevivientes de Dachau quedara abandonado en la huida. En los años siguientes, Fuchs eligió no hablar sobre el infierno que había atravesado: el gueto, Auschwitz, el exterminio de toda su familia. Tuvieron que pasar cuatro décadas y un viaje conmovedor para que empezara a contar esa historia públicamente y también a escribir. Muchas de esas reflexiones conforman ahora el libro Dilemas de la memoria. En esta conversación con Página/12, Fuchs habla de los años que siguieron a su llegada a ese galpón, de la posibilidad de construir un futuro después de Auschwitz. De su segunda vida.

Era mayo de 1945 y en Baviera caía aguanieve. Intentando escapar del avance de los aliados, los alemanes habían sacado a quienes aún sobrevivían en Dachau –gente desnutrida y enferma– y los habían subido a vagones que se usaban para trasladar ganado. El viaje, lento, se detenía con cada incursión aliada. Los alemanes se retiraban cuando se acercaban los aviones y reaparecían horas más tarde. Hasta que la locomotora fue bombardeada y ya no volvieron.

Fuchs bajó del vagón junto con los demás. Tenía 21 años y sólo pesaba 38 kilos. Padecía tifus y tuberculosis; sus pies hinchados casi no le permitían caminar. Se arrastró como pudo unos quinientos metros, hasta una granja habitada por alemanes. Entró en un galpón y vio una parva de heno. Allí se tendió y se quedó dormido. En ese lugar, pensaría después, fue donde renació, en la más absoluta soledad.

Al día siguiente lo encontraron los habitantes de la granja. No le dijeron ni le preguntaron nada. Le dieron comida y una cama ubicada en lo que eran dependencias para los trabajadores. Fuchs no sabe cuántos días pasó allí: quizás dos o tres. Luego lo subieron a una carreta y lo llevaron hasta Saint Ottilien, un antiguo monasterio transformado en hospital. Recién ahí las enfermeras le sacaron la ropa, lo lavaron, rasuraron y desinfectaron. Le dieron un pijama limpio y una cama en una enorme habitación. Fue entonces cuando dijo una frase que rondaría por su cabeza años después.

–Ahora ya me puedo morir tranquilo.

¿Por qué esa frase cuando lo peor había terminado? Quizá, supone, porque en los últimos días del campo había convivido con montañas de cuerpos y tenía pánico de morir en esas terribles condiciones.

–Me salió así. A veces en Dachau uno se despertaba y decía “ojalá estuviera muerto”. Mucha gente me pregunta cómo me salvé y yo digo que mis padres fueron condenados a morir y yo fui condenado a vivir. Simplemente no podía morir.

Pero el instinto de supervivencia funcionó y ya en esos primeros días en el hospital se empezaron a tejer lazos.

–Los nazis nos habían sacado todo: la familia, el cuerpo, pero no podían sacarnos lo poco de humano que quedó. Eso no lo pudieron eliminar. Enseguida en el sanatorio se organizaron diferentes grupos: los religiosos, los socialistas, los comunistas. En poco tiempo ya había un diario en idish.

A través de su partido, el socialista Bund, Fuchs consiguió una visa para viajar a Estados Unidos. En el tiempo que estuvo en Alemania antes de partir hizo algunas averiguaciones sobre el final de su familia. No es que tuviese expectativas de encontrar a alguno con vida: en Auschwitz, dice, las cosas eran claras. Pero necesitaba saber, así como después necesitó callar.

Lodz, Auschwitz, Dachau

Antes de la guerra, en la ciudad polaca de Lodz había 250 mil judíos, sobre una población de 750 mil personas. Un tercio de los habitantes que, prácticamente, desapareció. La transformación fue paulatina tras la invasión alemana. Primero los obligaron a usar la estrella amarilla, luego se decretó que un sector de la ciudad se convertiría en gueto para los judíos. En principio fue semiabierto, pero más tarde se cerró con alambre de púas y garitas con guardias y ya nadie pudo entrar ni salir.

Los Fuchs estuvieron en el gueto cuatro años. Pese a las privaciones que pasaron –el hambre, el frío, las enfermedades, el aislamiento–, esa época sería recordada como un paraíso en comparación con lo que vino después.

En 1944 los alemanes decidieron “liquidar” el gueto. Junto con sus padres y sus dos hermanas menores (al hermano mayor lo habían llevado a trabajar a un campo), Jack se escondió en una pequeña habitación tapada con un armario, pero alguien los delató y los encontraron. La deportación tuvo lugar a principios de agosto de 1944. El recuerda que llevaron hasta el tren unas pocas cosas, entre ellas su álbum de estampillas. En Auschwitz los separaron: mujeres por un lado, hombres por otro.

–A esa altura, ya no había secretos. Lo decían directamente: la gente iba al horno. Ni siquiera hablaban de gas. Esa fue la primera vez en mi vida que yo me desmayé. Un amigo me dio una patada. “Levantate, Yankele –me dijo–, si no vas al horno.”

Jack fue “seleccionado” para trabajar y esquivó la muerte. Mucho después supo que también su madre había sido “seleccionada”, pero no quiso separarse de sus hijas de 8 y 13 años y falleció con ellas. El estuvo en Auschwitz un tiempo que hoy se le hace confuso –seis días, quizá diez– hasta que fue trasladado a Dachau.

–Yo siempre me sentí mal porque cuando íbamos a los vagones escuché que decían “qué suerte, salen”. Sentí algo, no podría decir alegría, pero era algo agradable. Y me molestaba: ¿cómo puedo sentir esto, pensaba, si acabo de perder a toda mi familia? Muchos años después un psicoanalista me dijo que no sentía alegría: que era como si alguien me hubiera estado apretando el dedo con una tenaza y de pronto me soltara. Eso era.

Pero aún sufriría ocho meses en Dachau, donde las condiciones fueron deteriorándose día a día. Pronto la comida empezó a ser insignificante, se desataron las epidemias y ya nadie creía en la posibilidad de sobrevivir. Era, dice Fuchs, como estar enterrados vivos.

Así estaba cuando los alemanes los abandonaron en un vagón de carga en Baviera, cerca de ese galpón donde empezó su segunda vida.

Vivir con la valija

En Alemania Fuchs superó milagrosamente el examen médico que le hicieron los norteamericanos antes de embarcarse, algo que quizá sucedió porque no tenían equipo para hacer radiografías. Pero no estaba curado de la tuberculosis y dos semanas después de llegar a Nueva York lo llevaron a un médico. En la sala de espera conversó en idish con la secretaria, que a poco de hacerle las primeras preguntas se puso a llorar.

–No sé por qué, yo sólo le dije que había venido de Alemania en barco.

El médico le hizo placas, le mostró las cicatrices en sus pulmones y le aconsejó internarse en un sanatorio en las afueras de la ciudad.

–Creo que eso fue lo peor que me podían hacer: otra vez encerrado. Estuve ahí seis meses. No había ningún medicamento en ese momento, sólo descansar y tomar aire. En lugar de enviarme a ese lugar, tendrían que haberme mandado a hacer terapia: eso me hubiera ayudado.

La organización que lo recibió en Nueva York le había preguntado antes que nada si tenía a alguien en alguna parte del mundo. Jack mencionó a un par de tíos en Argentina y a una tía en Santiago de Chile. Al cabo de un tiempo fueron localizados, pero aunque lo invitaron a venir, él prefirió quedarse en Estados Unidos.

–Me demoró mucho tiempo saber cuál fue el motivo. Creo que yo pensaba que iba a venir y mis tíos me iban a preguntar qué había pasado con mis padres, con mis hermanos. Que me iban a decir “¿cómo están todos muertos y vos vivís?” Tenía miedo. Pero eso lo supe más tarde.

Una vez que salió del sanatorio empezó a trabajar en un taller de confección y por la noche completó el secundario. También hizo cursos y fue especializándose en sistemas de producción. En esa etapa Fuchs vivió siempre con una valija en las manos: saltando de un lugar a otro. Dice que no se mostraba afectado por su pasado.

–Es algo que veo ahora, después de muchos años de terapia en Argentina. Yo me mandaba la parte de que estaba bien. Decía “yo recuerdo, sí, a veces lloro, pero no me afecta”. Tenía novias, amigos... Pero algo había quedado: una inquietud de la que yo mismo no me daba cuenta. Antes yo creía que si alguien se reía a carcajadas significaba que era feliz. Ahora que tengo 82 años reconozco cuando una persona ríe, no porque es feliz, sino porque es histérica, cuando corre, no por curiosidad, sino porque no puede estar sentado. Yo corría, viajaba por Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Israel... Todos me admiraban por lo que hacía, pero todo era falso. Aparentemente no podía hacer una vida normal. Debía ser el miedo.

Después de diez años en Estados Unidos, vino a la Argentina de visita. Su viaje coincidió con la caída de Perón y recuerda el tumulto en las calles.

–Mis tíos no me preguntaron qué pasó con mi familia ni yo se los conté.

Regresó a Nueva York y siguió con su vida trashumante. Recién en 1963, después de vivir un tiempo en Venezuela, decidió volver a la Argentina. Era una época en la que no estaba muy bien. Algo le faltaba, dice.

–No sé, me sentía incómodo. Estaba siempre corriendo, tenía casi cuarenta años y pensaba que estaba solo y ya no iba a tener hijos.

Una serie de circunstancias en esa visita lo decidieron a quedarse, pero sobre todo una: conocer a quien sería su mujer, Ivonne, una francesa que había pasado la guerra en Suiza y cuya familia había fallecido. Jack consiguió trabajo aquí y empezó a hacer terapia. Pero la inquietud aún persistía: cuando se casaron, le sugirió a Ivonne que se fueran a Nueva York. Ella lo disuadió.

–Vos ya viajaste mucho –me dijo–. Mejor quedémonos.

Jack se ha preguntado a sí mismo por qué se casó con Ivonne, mientras que en sus relaciones previas había evitado ese compromiso.

–Aparentemente yo tenía miedo de entrar en una familia, porque soy un bicho raro, que trae una desgracia. Creo que me casé con Ivonne porque, como yo, ella no tenía a nadie. Era muy inteligente –sonríe– y podía aguantar todas mis locuras.

Entre esas locuras estaba su dificultad para afincarse en un sitio. Cuenta que vivían en un departamento alquilado y que luego del nacimiento de Marianne, su hija, Ivonne sugirió comprar una propiedad en cuotas. Pero él se resistía.

–Al final cuando lo compramos lo eligió ella. Me pidió que al menos fuera a verlo, pero le dije que no. Estaba seguro de que había elegido muy bien.

Jack montó una pequeña fábrica de confección de lencería e Ivonne daba clases de francés. Se arreglaban bien. Pero ella enfermó y murió en 1989: demasiado pronto. Fue la primera vez que Jack asistió a un entierro.

Hablar y callar

Dice Fuchs que ni siquiera con su esposa hablaba sobre su pasado: con ella era algo sobreentendido. Tampoco con Marianne.

–Es un caso interesante para un psicólogo. Cuando mi hija tenía dos o tres años, vio algo de la guerra por televisión y me dijo “papi, vos no mires”. Yo jamás había hablado con ella. Aparentemente hay una transmisión por ósmosis.

Ha discutido con quienes creen en la necesidad de insistir sobre lo sucedido con los hijos, para que recuerden. El lo rechaza: dice que ya bastante tienen con ser hijos de sobrevivientes. Ni siquiera sus tres nietas –la mayor de las cuales hoy tiene quince años– lo interrogan sobre la historia. Saben, dice, perciben, pero no preguntan. ¿Será que temen dañarlo haciéndole recordar momentos de dolor? El duda.

–Es raro. Un chico de ocho o nueve años no piensa que me puede lastimar.

La decisión de contar la historia que había silenciado durante cuarenta años se dio después de un viaje a Washington en 1983. Ese año muchos sobrevivientes se reunieron en torno del proyecto del Museo del Holocausto. Dice Fuchs que la ceremonia fue muy conmovedora.

–Se puso la piedra fundamental para el museo. Para mí fue como una lápida: nadie en nuestras familias tiene lápidas, ni sabemos dónde están. Ahora había una lápida, aunque fuera colectiva. Cuando regresé del viaje estaba lleno de emociones y tenía ganas de compartir. Supongo que se mezcló con muchos años de psicoanálisis.

La primera vez que contó la historia en un medio fue en una entrevista concedida a Página/12, hace ya quince años. Dice que después de que se publicara los amigos con los que jugaba al tenis cada semana en el club Hacoaj lo llamaron anonadados: no podían creer que nunca les hubiera dicho nada de todo ese horror.

–A veces uno no sabe qué decir, cómo explicar. Primo Levi escribió lo que una persona dijo en Auschwitz: que si alguien se salvaba y contaba, nadie lo iba a poder creer. Por eso, yo nunca quise contar atrocidades.

Durante los años que siguieron habló cada vez que se lo pidieron: en escuelas, conferencias, entrevistas. Pero últimamente, dice, se siente alejado de lo que pensaba antes sobre la importancia de trasmitir lo vivido. Desencantado.

–Creo que no tiene ningún valor entrevistar a la víctima: habría que entrevistar al victimario. Una persona en una hora se convierte en víctima. Y no tiene nada para decir, no hay nada que aprender de ella. El victimario tiene un plan: cómo eliminar a la gente, cómo torturarla...

Reconoce, sí, la importancia de contar para el registro histórico, para que se conozca lo que pasó, pero ya no piensa que sirva hacia el futuro.

–La gente no aprende nada del pasado: el hombre no tiene herramientas para evitar una próxima guerra.

A veces se sorprende por la insistencia con que lo buscan, como si fuera dueño de algún misterio, de un secreto de la supervivencia.

–La gente deposita cosas en mí. Piensan que es una ironía cuando yo digo que sobreviví porque sobreviví. Pero yo no hice nada. No soy ningún héroe, lo único es que no tenía el coraje de matarme.

De regreso

Fuchs volvió dos veces a la ciudad donde nació. La primera fue con Ivonne, a mediados de los ochenta. Había pensado quedarse a pasar la noche, pero a poco de llegar se quiso ir. Dice que estaba como anestesiado. Recorrió la zona donde había estado el gueto y vio que nada lo recordaba: ni un museo, ni una placa: como si allí nunca hubieran vivido miles de judíos. El único lugar donde había huellas de su presencia era el cementerio. Se fue enseguida. El segundo viaje fue con Marianne, hace cuatro años. Esta vez pudo caminar horas con ella, mostrándole cada lugar.

–Dónde vivían mis amigos, dónde estaba la escuela, dónde comenzó el gueto. Hasta estuve sentado con ella en la peatonal, comiendo pizza. Jamás hubiera podido pensar unos años antes que era posible. Marianne dice que su vida se divide en antes y después de ese viaje.

Luego tomaron un tren hacia Cracovia, que está junto a Auschwitz. El mismo recorrido que Jack hizo con su familia cuando fueron deportados. En ese viaje, su hija le tomó una foto. La cara de Jack se ve crispada, tristísima.

–Yo no sabía que tenía esa cara.

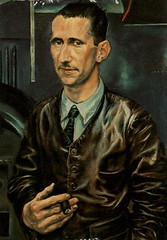

Junto a esa foto, en su biblioteca, hay otra, que se reproduce en estas páginas. La única foto que tiene de su familia: ahí está él con sus padres, su hermano mayor y una de sus hermanas. La menor aún no había nacido. Pudo tener esa foto gracias a sus tíos, a quienes sus padres se la enviaron antes de la guerra. En la misma biblioteca hay más fotos: de Marianne y sus nietas.

Jack recorre la casa mostrando otras imágenes de las chicas. Y sus dibujos, que ha pegado en las paredes. Señala un retrato de él que hizo la mayor de sus nietas, con un notable parecido al original. Dice que lo muestra con orgullo de abuelo. Un orgullo que se percibe cada vez que habla de todas ellas, de esas mujeres que iluminaron ésta, su segunda vida.

© 2000-2006 www.pagina12.com.ar|República Argentina|Todos los Derechos Reservados

http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/sociedad/3-72766-2006-09-10.html

The Independent:

9/11 - A bloody legacy

The 'war on terror', which began with the attacks on the US, is five years old. It has killed tens of thousands and drawn British troops into conflicts around the world - but in Afghanistan, where the first victory was won, all the gains are in danger of slipping away

By Raymond Whitaker in London and Tom Coghlan in Kabul

Published: 10 September 2006

The West is fighting a crucial battle in the "war on terror", and British troops are in the front line.

British-led Nato forces are engaged in a make-or-break struggle in southern Afghanistan, where the biggest ground offensive in the history of the alliance was launched in Panjwayi district, near Kandahar, just over a week ago. The aim is to throw back a resurgent Taliban.

Yesterday, Nato said Operation Medusa had killed 40 Taliban fighters in the previous 24 hours, and several hundred more were surrounded. If the offensive succeeds, it will be a first step towards reversing the tide of instability that has engulfed an increasing area of the country and led to the deaths of 19 British military personnel this month (14 of them in an air crash).

But commanders admit it is an extremely close-run thing: if the offensive fails, the position of British forces in neighbouring Helmand province - where they were deployed this year with the then Defence Secretary, John Reid, expressing the blithe hope that they could complete their three-year mission "without firing a shot" - could become untenable.

Afghanistan was where the first victory in the "war on terror" was won. Less than three months after the 9/11 horror, al-Qa'ida's Taliban sponsors had been overthrown and Osama bin Laden was on the run. Yet tomorrow, when the fifth anniversary of the attacks on New York and Washington are commemorated, the world will reflect that Bin Laden remains at large somewhere along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Mullah Omar, the Taliban's one-eyed leader, has also evaded capture, and his movement is regaining strength. What has gone wrong?

For General Sir Michael Rose, who led the SAS and commanded British forces in Bosnia, it is simple. "Having defeated the Taliban in 2001, the West then mistakenly shifted its effort and resources to Iraq, leaving most of Afghanistan insecure," he said. "This has allowed the Taliban to return." In other words, not only have gains in the real "war on terror" been dangerously eroded, the reckless detour into Iraq has made things worse. Far from hunting Bin Laden down, the West has been forced to prevent his allies re-establishing a foothold in Afghanistan.

After months of public denials by commanders and politicians, they are finally admitting that military forces in southern Afghanistan are stretched. Yesterday, as security forces in Kabul cleared the debris of the worst suicide bombing in the Afghan capital for two years - in which at least 16 people, including two US soldiers, died - senior military commanders from all 26 Nato nations were meeting in Warsaw to answer an appeal from Nato's supreme commander, US General James Jones, for up to 2,500 more troops at what he called "this decisive moment".

The Taliban cannot hope to win a head-on clash against Western forces, though General Jones admitted last week that the alliance has been surprised by the ferocity of the movement's response. The tactical initiative has been with the insurgents, who have kept Nato forces off-balance with hit-and-run attacks, suicide bombings and frontal assaults on isolated outposts in northern Helmand, where small British detachments have sustained a steady trickle of casualties as they fight off attackers.

"The fighting is extraordinarily intense. The intensity and ferocity ... [are] far greater than in Iraq on a daily basis," the commander of British forces in Helmand, Brigadier Ed Butler, said this month. Instead of calming an area by their mere presence, British soldiers have become a magnet for insurgents. Afghan forces remain unreliable, while the local population is equivocal, at best. The only secure point is the main British base, Camp Bastion, isolated in the desert north-west of the provincial capital, Lashkargar. One senior Western diplomat in Kabul called the situation "dire".

British and Irish aid agencies working in Afghanistan have been producing monthly reports on the state of the country since well before 2001, and the latest one makes grim reading. "The underlying security situation affecting the day-to-day mobility of the population, as well as the operations of the government and of the aid and reconstruction communities, is deteriorating in many areas," it says. "The Taliban have an increasing presence at the local level in large areas of the south and are in a strong position to threaten security, intimidate and also build a support base."

The big push in Kandahar province, where Canadian forces are doing most of the fighting, is aimed at regaining the advantage. The Canadians have chased the Taliban away in Panjwayi district many times before, only for the insurgents to seep back once Nato forces have gone. This time, officers say, the aim is to hold the ground once it has been captured. That, however, requires boots on the ground - and they are desperately short.

At the end of this month, Nato's commander in Afghanistan, Britain's Lieutenant-General David Richards, takes responsibility for all foreign forces in the country apart from a handful of Americans engaged in the hunt for al-Qa'ida leaders. General Richards has already indicated that he aims to take a more subtle approach than the gung-ho Americans, whose aerial bombardments are thought to have caused high civilian casualties.

In what is known as an "ink-spot" strategy, the intention is to start developing "Afghan development zones" in the south. Where the security situation has been stabilised, there will be a deluge of aid - first in the form of "quick impact" projects, and later of more sustainable development assistance. Nato and special forces will range around these zones, harrying the Taliban and preventing them upsetting the security balance within the safe areas. In the next stage, the roads between these zones will be gradually secured and the influence of the government extended around them. Like ink spots on a piece of blotting paper, the zones will grow until they merge together.